The Peoples of Utah, ed. by Helen Z. Papanikolas, © 1976

“Blacks in Utah History: An Unknown Legacy,” pp. 115–40″

by Ronald G. Coleman

This essay is gratefully dedicated to Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead, a descendant of three Black pioneer families and related through marriage to others. She has contributed greatly to this writer’s research and to that of others in quest of the role of Blacks in Utah history.

The history of Blacks in Utah is a microcosm of the history of Blacks in the United States. Black experience in Utah began during the exploration and fur-trapping period. James P. Beckwourth, a mulatto whose mother may have been a slave, is the best-known Black of this period. A trapper for the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, guide, Indian fighter, and hunter, Beckwourth is a legendary figure in this early history of the Far West. He was a participant in the Seminole and Mexican War, the California gold rush, and for several years lived with the Crow Indians.

Beckwourth came to Utah between 1824 and 1826. For several years he traveled in and out of Cache Valley and the Salt Lake Ogden areas trapping, hunting, and exploring. Among his comrades were Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, James Clyman, William Sublette, and Jedediah Smith. Fortunately for historians, Beckwourth left a record of his life and adventures; in addition to providing information about his life, the work gives valuable detail about the history of the Far West. Scholars have disagreed as to the veracity of parts of Beckwourth’s autobiography. In keeping with the tradition of mountain men, Beckwourth was known to stretch the truth, especially when glorifying his own accomplishments. The main faults of his autobiography were due to lapses of memory and misuse of statistics.1

As historian Hubert Howe Bancroft wrote:

Beckwourth was by no means a bad man, though he had his faults, the greatest of which was being born too late. He should have swum the Scamander after Grecian horses, captured Ajax when calling for light, or scalped Achilles in his tent. Then had not been denied him the honor of dying like a Roman on his shield in a lightning of lances, or a storm of Blackfoot braves.2

Other Blacks were in Utah at approximately the same time as Beckwourth, long before Mormon settlement. One adventurer, Jacob Dodson, was a member of two of John C. Fremont’s expeditions into Utah and other parts of the West between 1843 and 1847. Dodson was about eighteen years old when he volunteered to accompany the Fremont expedition. The financial report of the exploration lists him as a voyager and shows payment of $493 for his services between May 3, 1843, and September 6,1844. Fremont said Jacob Dodson “performed his duty manfully throughout the voyage.”3

Blacks, therefore, were m Utah almost a quarter of a century before the arrival of the Mormons in 1847; however, permanent Black settlement began with the pioneers and established the foundation for today’s Black community. Approximately one hundred fifty descendants of the early Black pioneers presently live in Utah.4

Three Black men entered Utah with the initial Mormon pioneer group. Folk tradition says that Green Flake drove the wagon that brought Brigham Young into the valley. Oscar Crosby and Hark Lay also appear in various historical works on the pioneers. Their names are engraved along with those of other first pioneers on a tablet on the Brigham Young Monument at the intersection of Main and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City.5

Except for these three men, the Black pioneers of Utah have remained relatively anonymous in the annals of Utah history. Black pioneers were both slave and free, Mormon and non-Mormon. They shared the experiences of journeying to a new land and participating in its settlement and subsequent development.

The 1850 Census of Utah Territory indicates the presence of fifty Blacks in Utah. Of this number, twenty-four are listed as free and twenty-six as slaves.6 In most instances census schedules do not include the names of those Blacks in bondage. However, the 1850 Census of Utah Territory lists the names of Blacks in bondage and notes they were enroute to California.7 Thus, one might be led to believe that with the removal of those twenty-six individuals, Utah’s slave population was eliminated. This is inaccurate; the 1860 Census indicates the presence of fifty-nine Blacks in Utah, twenty-nine of whom were slaves.8 The Utah territorial legislature in 1852 had passed a law that recognized the legality of slavery in the territory.9 Acceptance of Black bondage in Utah began with the settlement of Mormon pioneers in 1847 and became illegal when the United States Congress abolished slavery in the territories in June 1862.10 While there is evidence of some masters emancipating their slaves before 1862, it appears that the majority did so only after slavery was abolished by law.

Mormon masters had come from the South and leaving there brought some of their slaves with them.11 Black slaves also accompanied non-Mormons to Utah.12 The exact number of Black slaves in Utah is unknown; some pioneer companies did not differentiate between slaves and free Blacks.13 In addition, the census report of 1850 is incorrect in reporting the number of Blacks, free or slave in the Utah territory.14

There is more information about Green Flake, one of the three Blacks accompanying the initial pioneer group into Utah, than there is about either Oscar Crosby or Hark Lay. This is largely because of his residing in Utah longer than they did. Crosby and Lay were members of a group of slaves taken to San Bernardino, California, in 1851 by Mormon masters who went to colonize the area.15 Because California law prohibited slavery, the Blacks became free.16

Green Flake was the slave of James M. Flake, a southerner who had moved from North Carolina to Mississippi. In 1843 James Flake and his family joined the Mormon church, and shortly thereafter he sold or emancipated the majority of his slaves and moved to the Mormon settlement in Nauvoo, Illinois.17 Flake took Green and Liz, a young Black girl who was Mrs. Agnes Flake’s personal maid, to Nauvoo with the family. As the Mormon pioneers made preparations for the journey to Salt Lake in 1847, James Flake sent Green to help Brigham Young’s pioneer company on the journey.18 Green helped the pioneers in planting crops and building homes. Then he returned east with others to aid the Mormon immigrants coming west. Between 1848 and 1850 Green married Martha Crosby and became the father of two children, Lucinda and Abraham. For a while Green Flake worked for Brigham Young, and by 1860 he had acquired property and was living with his family in Union, Utah. Although he moved to Idaho in 1885, he continued to correspond with his friends in Utah and journeyed to Salt Lake to participate in the pioneer celebration of 1897. When Green died, his body was returned to Utah for burial next to Martha in the Union cemetery.19

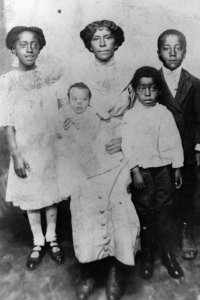

Martha J. Perkins Howell, granddaughter; Lucinda Flake Stevens, daughter; Belle Oglesby, granddaughter, all descendants of Green Flake who allegedly drove Brigham Young’s wagon into the Salt Lake Valley in 1847.

Among the Blacks coming to Utah with Mormon pioneers at least three families were known to be free. The James family arrived in Salt Lake in 1847 and consisted of Isaac and Jane along with their children, Sylvester and Silas. Jane Manning James was the matriarch of Utah’s early Black community. She and her brother, Isaac Manning, had lived and worked in the Nauvoo home of Joseph Smith, the founder of the Mormon church.20 Although Isaac Manning did not arrive in Salt Lake until 1893, both he and his sister Jane were accorded a special status within the local community.21

After the James family settled in Salt Lake, they went into farming. Although they were far from being financially secure, by 1865 the family’s real estate and personal property were valued at $1,100.22 Sylvester James, the oldest of the children, was listed in 1861 as a member of the Nauvoo Legion and was in possession of his ten pounds of ammunition and musket. He later married Mary Perkins and was a successful farmer. Sylvester James is the only Black listed in Frank Esshom’s Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah.23

The financial success of Isaac and Jane did not prevent them from having personal difficulties, and by 1870 they had separated. Only two of her seven children outlived her, and many of her grandchildren died at an early age. Despite her difficulties, Jane Manning James maintained her poise and self-respect. When she died in 1908, newspapers noted her death and President Joseph Fielding Smith spoke at her funeral.24

In 1847 a mulatto named Elijah Abel and his family journeyed to Utah with other Mormons. Abel had been baptized in September of 1832, ordained an elder in the Melchizedek priesthood on March 3, 1836, and made a member of the Nauvoo Seventies Quorum in 1839. His membership certificate was renewed in 1841 in Nauvoo and again in Salt Lake City. The Abels also lived in Ogden for a short time. A carpenter by trade, Abel contributed his work to the building of the Mormon temple in Salt Lake City where he and his wife Mary Ann managed the Farnham Hotel. Almost forty years after arriving in Utah, Abel went on a mission for his church to Canada, proselytizing in the United States on the way. A year later, in 1884, he returned and died shortly afterwards “in full faith of the gospel.”25

Fredrick Sion, a mulatto from England, came to Utah in 1862. Along with his wife, Ellen, and daughter, Eliza, Sion sailed on the ship William Tapscott which arrived in New York in June 1862. The family then made the long journey to Utah and settled in Millville where Sion continued to work as a shoemaker. Three more children had been born by 1870.26

The treatment of Black slaves in Utah can be seen in “An Act in Relation to Service.” Approved in 1852, the law recognized the legality of slavery and clearly explained the responsibilities of both the slave and slave master.

Slave holders coming into the territory were required to file evidence of lawful bondage with the probate court, and any transfer of slaves to another master or removal of them from the territory required court approval and the consent of the slaves themselves. Four sections of the act dealt with the issues of miscegenation; food, clothing, and shelter; punishment; and education:

Sec. 4. That if any master or mistress shall have sexual or carnal intercourse with his or her servant or servants of the African race, he or she shall forfeit all claim to said servant or servants to the commonwealth; and if any white person shall be guilty of sexual intercourse with any of the African race, they shall be subject, on conviction thereof to a fine of not exceeding one thousand dollars, nor less than five hundred, to the use of the Territory, and imprisonment, not exceeding three years.

Sec. 5. It shall be the duty of masters or mistresses, to provide for his, her, or their servants comfortable habitations, clothing, bedding, sufficient food, and recreation. And it shall be the duty of the servant in return therefor, to labor faithfully all reasonable hours, and do such service with fidelity as may be required by his, or her master or mistress.

Sec. 6. It shall be the duty of the master to correct and punish his servant in a reasonable manner when it may be necessary, being guided by prudence and humanity; and if he shall be guilty of cruelty or abuse, or neglect to feed, clothe, or shelter his servants in a proper manner, the Probate Court may declare the contract between master and servant or servants void, according to the provisions of the fourth section of this act.

Sec. 9. It shall further be the duty of all masters or mistresses, to send their servant or servants to school, not less than eighteen months between the ages of six years and twenty years.27

The seeming benevolence contained in certain parts of the act when compared with similar legislation in regards to Indian slavery demonstrates a higher regard for Indians than for people of African descent. The preamble to “An Act for the Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners” says the act “…will be most conducive to ameliorate their condition, preserve their lives, and their liberties, and redeem them from a worse than African bondage?”28 Furthermore, the masters of Indians were obligated to send Indians between the ages of seven and sixteen to school three months of each year if a school was within the area of residence.29 Finally, the restrictions against sexual relations between all Blacks and whites were not applicable to Indians; some Mormons were induced to take Indian wives in the early period of colonization. That both acts were adopted within a month of each other shows a greater aversion to people of African descent.30

Slave owners also had no reservations about selling their slaves, and the local courts recognized the right of a slave owner to secure his property. The legality of such transactions is attested to by numerous examples. Alexander Bankhead was originally brought to Utah by George and John Bankhead and later purchased by Abraham O. Smoot and taken to Provo.31 Marinda Redd, who later be-came the wife of Alexander Bankhead, initially journeyed to Spanish Fork with John Hardison Redd, his family, and five other Black slaves.32 Later she became the property of Dr. Pinney, a resident of Salem, Utah.33 In August 1859 “Dan,” a twenty-six-year-old Black man was sold by Thomas S. Williams to William H. Hooper. Williams had purchased Dan a year earlier from Williams Washington Camp for $800.34 Perhaps the reason for Williams Camp selling Dan arose from a court case in June 1856. Camp was accused of kidnapping Dan, who earlier had run away from him. Upon proving that Dan was his slave, Camp was acquitted of the kidnapping charge 35

An 1899 editorial in the Salt Lake City Black newspaper, the Broad Ax, records the reminiscences of two Black pioneers, Alex Bankhead who arrived from Alabama in 1848 and his wife who was born in North Carolina and came to Utah in 1850.

She was the property of a gentleman by the name of Redd. She, in company with a number of other slaves, were on their way to Utah; and while passing through the State of Kansas, during the dark hours of the night, the majority of them made good their escape, which was a great loss to their owner But Mrs. Bankhead was not so successful in that direction, and she was brought on to Utah…They both have a very distinct recollection of the joyful expressions which were upon the faces of all the slaves when they ascertained that they had acquired their freedom through the fortunes of war. At that time many negroes, according to Mr. Bank-head’s statement, “Left Salt Lake City and other sections of the Territory, for California and other states”…He informed us that when this city was in its infancy, the slaves always congregated in a large room or hall on State street almost opposite the city and county building. There they would discuss their condition, and gaze in wonderment at the lofty mountains, which reared their snowy peaks heavenward, and completely forbade them from ascertaining how they could make their escape back to the South, or to more congenial climes. For we were assured that their lives in the then new wilderness, was far from being happy, and many of them were subjected to the same treatment that was accorded the plantation negroes of the South. Mr. and Mrs. Bankhead now own a little home, including twenty acres of land. They are both devout and strict Mormons.36

The interest of slaves in the progress of the Civil War and what the outcome might mean for their condition is shown by Sam Bankhead’s continuing desire for news from the East. He was heard to comment, “My God, I hope de Souf get licked.”37 For many slaves the wish for freedom did not imply negative feelings toward their masters. Freedom meant that they could be their own masters.

Although many former slaves left the area, others remained in Utah and together with the early free Black residents and new arrivals sought to elevate and improve their condition in Utah. These people intermarried and lived in close proximity to one an-other in Union, the east Millcreek area, and the Eighth LDS Ward, now called Central City.38

The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and the expansion of railroads from Utah to other states greatly improved the economic opportunities for individual investors and corporate concerns. Not only did the railroads profit but the improved transportation network was valuable to mining and agricultural interests. Black workers, like other Americans east of the Missouri, responded to new employment opportunities with the railroads.

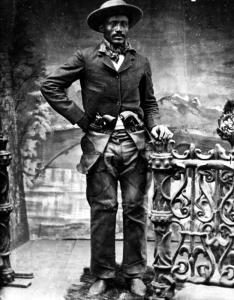

During this post-Reconstruction period, Black involvement in the settlement of the West continued in earnest?the awareness of its extent is but a recent addition to western history. The Black cowboy quickly became myth. There were at least two Blacks who worked the range in the Brown’s Hole area on the Utah, Wyoming, and Colorado borders. Albert “Speck” (because of his freckles) Williams operated a ferry on the Green River.39 Isom Dart, known primarily as a cattle rustler, was an outstanding bronco-buster. “I have seen all the great riders,” a westerner said in William Katz’s The Black West, “but for all around skill as a cowman, Isom Dart was unexcelled…He could outride any of them; but never entered a contest.”40

Isom Dart, cowboy in the Brown’s Hole area

Despite his reputation for stealing cattle, Isom Dart appears to have been a man of character. Joe Philbrick, a deputy sheriff from Wyoming, went to Brown’s Hole to arrest Dart on suspicion of cattle rustling. While returning to Rock Springs, Philbrick was badly injured in an accident. Rather than escaping, Isom gave Philbrick what help he could and returned him to Rock Springs. After leaving Philbrick in the hospital, he turned himself in to the local authorities. At his trial Philbrick appeared as a character witness, the charges were dropped, and Isom returned to Brown’s Hole.41

Another Black cowboy, and one of the few to leave an account of his life on the trail, was Nat Love. His autobiography is titled The Life and Adventures of Nat Love: Better known in the Cattle Country as “Deadwood Dick.” On his retirement from the cowboy trail, Deadwood Dick worked as a porter for the Pullman service. For a period in the 1 890s he lived with his family in Salt Lake City.42

In the last quarter of the nineteenth century the military brought many Blacks to Utah. In 1869 Congress created two Black infantry regiments and two Black cavalry regiments. All four of these units saw action in the West for over thirty years after the Civil War.43 Three of the four units, the Ninth Cavalry, the Twenty-fourth Infantry, and the Twenty-fifth Infantry served in Utah.44 To the Indians, the short wool-like hair of the Black soldiers resembled the shaggy mane of the buffalo. Hence, the Indians called the Black soldiers of the Ninth and Tenth cavalries the “buffalo soldiers.”45

Because of difficulties with Ute Indians, authorities in Washington decided to establish a military post on the Uintah frontier. The post was named Fort Duchesne, and in 1886 two troops of the Ninth Cavalry arrived with four companies of infantry to man the fort. In addition to building the post, the soldiers were charged with protecting and controlling the Indian populations of eastern Utah, western Colorado, and southwestern Wyoming. The Black soldiers were stationed at Fort Duchesne for approximately twelve years. With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, members of the Ninth Cavalry were sent to Mobile, Alabama, to prepare for the journey to Cuba.46 Some members of the Ninth Cavalry were sent to Salt Lake City’s Fort Douglas in June 1899.

The placement of members of the Ninth Cavalry at Fort Douglas in 1899 was not the first time Black soldiers had been stationed at the fort. In October 1896 the Twenty-fourth Infantry arrived for duty there. For the first time in history, the United States Army had stationed a Black unit in an area with a substantial Black population within a large white population. Before this, Black soldiers had been stationed in isolated areas. With all of the companies intact, the number of men in the Twenty-fourth Infantry was approximately four hundred fifty. The members of the Twenty-fourth regiment were elated when they first learned of the transfer to Fort Douglas. Having spent many years in the Arizona-New Mexico region, the men wanted a more pleasant location. Fort Douglas, at the time, was considered an ideal location by all soldiers, Black and white.

The joy of the Black soldiers was not shared by many of Salt Lake’s white residents. The Salt Lake Tribune and Sen. Frank J. Cannon did everything possible to persuade officials in Washington not to send Black soldiers to Fort Douglas. An editorial in the Tribune questioned the character of Black soldiers and suggested that under the influence of liquor Black soldiers might become aggressive in the presence of white women.47 The Tribune and Cannon failed to change the minds of Washington officials. As members of the Twenty-fourth prepared to come to Fort Douglas, a letter written by Pvt. Thomas A. Ernest, of Company E, Twenty-fourth Infantry, appeared in the Salt Lake Tribune:

The enlisted men of the Twenty-Fourth infantry, as probably the people of Salt Lake City know, are negroes…They have enlisted to uphold the honor and dignity of their country as their fathers enlisted to found and preserve it…

We object to being classed as lawless barbarians. We were men before we were soldiers, we are men now, and will continue to be men after we are through soldiering. We ask the people of Salt Lake to treat us as such.”48

Within a relatively short time, the members of the Twenty-fourth developed close ties with the Salt Lake City community. Black and white citizens were entertained and impressed by the Twenty-fourth’s “outstanding band, crack drilling and the ability of many of its members in athletics, both track and baseball.” Chaplain Allan Allensworth, one of two Black chaplains in the United States Army at the time, was impressive. College educated and urbane, he sought to aid the members of the regiment in improving their educational skills and emphasized the importance of the soldiers’ maintaining good conduct. In addition, Allensworth was active in local affairs. On December 21, 1896, he met with Mormon church president Wilford Woodruff who welcomed the members of the Twenty-fourth Infantry to Salt Lake City.

During the Spanish-American War members of the Twenty-fourth saw duty in both Cuba and the Philippine Islands. Many Salt Lake and Provo residents, Black and white, turned out to bid them farewell when they left and a joyful welcome upon their return to Salt Lake. Upon completion of their duty in the Philippine Islands, the companies of the Twenty-fourth were dispersed to different parts of the United States.49 Several of the soldiers liked their experience at Fort Douglas and eventually made Salt Lake City their permanent residence.50

Since the turn of the century a majority of Utah Blacks have lived in the cities of Salt Lake and Ogden. Employment opportunities for Blacks have been greater in these cities and their surrounding areas. Despite the tendency of Blacks to settle in urban centers, wherever employment opportunities existed in other parts of the state, Black workers willingly moved there. In the period between 1920 and 1930, Carbon and Emery counties had a number of Blacks working in the coalmines and other related industrial activities.51 The Black population in these areas declined when employment was reduced.

For many years the majority of Blacks residing in Salt Lake and Weber counties were primarily employed in domestic and personal services for the civilian population. When Ogden became the railroad center for the Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, and other railroads, many Blacks, both local and new arrivals, found work. Railroads advertised widely for men to fill their various labor needs. Word was sent out through newspapers, by word-of-mouth, by correspondence between relatives and friends, and through cards handed out on streets by railroad agents. “Wanted 1,000 Men” the cards read, with the address of the railroad’s hiring office underneath the words. Between 1890 and 1940, the railroad was the most important employer of Blacks. Some of them worked in railroad roundhouses and on construction crews, but Blacks were mainly porters, cooks, and waiters for the railroads’ hotel and restaurant services.52 Fantley Jones, a forty-year resident of Ogden, recalls that he was living in Oklahoma when he received a letter from a cousin telling him that the Union Pacific railroad needed men, and if he could get to Kansas City, a ticket and job would be waiting for him. “I sold a calf and used the money to get to Kansas City,” Jones said. In Kansas City, Jones was hired as a cook by the railroad’s local agent, a man named Beanland, and put aboard a train to Ogden. Jones began learning his job on the way and remained as a cook for the Union Pacific until he retired in 1969.53

The influx of Black railroad workers required hotel and restaurant facilities, because white-owned services were barred to Blacks. In Salt Lake City, near the rail yards, several hotels, restaurants, and clubs, such as the Porters and Waiters Club, were operated by Blacks. Blacks in Ogden also provided similar services near the Union Pacific depot. Lonnie Davis and his wife owned the Royal Hotel where Blacks, temporarily in the area, stayed. Billy Weekly managed the Porters and Waiters Club.

Railroads, the military, and military-related activities influenced the further growth of Utah’s Black community. World War II with its increased number of military camps and defense plants provided employment for Blacks at Hill Air Force Base in Ogden, the Dugway Proving Grounds in Tooele, and other military installations in Utah.54

Blacks in Utah, like Blacks in many states, were excluded from participating in the general social and cultural life and consequently developed their own churches, fraternal organizations, a literary club, a press, and a community center. Blacks have participated on semi-professional baseball teams, sponsored by state industries since the early 1900s. (The Leggroan brothers are remembered as outstanding players of the 1920s. A teammate of one of the brothers on the Denver and Rio Grande Western team recalls, “He was a fine player and a gentleman. When we went out of town, he didn’t come with us.”55 The inference was that he would not cause embarrassment to the team by being refused service in restaurants and hotels.)

In the 1890s Trinity African Methodist Episcopal Church was the first Black church to be established and Calvary Baptist Church was founded shortly afterward. Both of these churches were located in Salt Lake City. Early in the century Wall Street Baptist Church was founded in Ogden.56

Black newspapers were first published in Utah during the late I 890s. The Democratic Headlight, published by J. Gordon McPherson, appeared briefly in 1899. The Tri City Oraclewas published for a few years by Rev. James W. Washington, pastor of the Calvary Baptist Church. The two most interesting Black papers were the Utah Plain Dealer, published by William W. Taylor, and the Broad Ax, published by Julius Taylor. The Broad Ax was discontinued in 1899 when Julius Taylor moved to Chicago. The Plain Dealer continued to appear until 1909.57 The two editors were continually arguing through their respective papers over which publication truly represented the best interests of the Black race. William Taylor supported the Republican Party and Julius Taylor, surprisingly, supported the Democratic Party.58 Besides waging their private war, both editors sought to inform the community of local and national news.

Every year the Black community celebrated Emancipation Day. The sponsor of this event was the Abraham Lincoln Club, a Black Republican organization.59 The Democratic counterpart was the Salt Lake Colored Political Club.60 Several of the old Black Mormon pioneers participated in the annual Old Folks Day celebration. There would be an annual free excursion to some point in the area for them.61 Many Blacks would turn out to watch and some took part in the celebration of the “Days of Forty?seven.”62

Blacks formed local lodges of the Odd Fellows and Elks. The Ladies Civic and Study Club of Salt Lake City, the Camelia Arts and Crafts Club, and the Nimble Thimble Club were three Black women’s groups. The Nimble Thimble Club was responsible for initiating the idea of building a community center for Blacks. The Nettie Gregory Community Center, named for an outstanding member of the club, was completed in 1964 at Seventh West and South Temple streets in Salt Lake City. Besides joining the various fraternal and social groups, Blacks often went to dance and to listen to the music at some of the local nightclubs. Dixie Land, the Jazz Bo, the Porters and Waiters Club, and the Hi Marine were places where Blacks and some whites went for entertainment.63 The well-known bandleader and arranger Fletcher Henderson and his brother Horace had a club north of Salt Lake City in the 1940s.64

Paul C. Howell was Salt Lake City’s first Black policeman and today his great-grandson, Jake Green, is a member of the Salt Lake City Police Department.65 D. H. Oliver was a Black attorney who was active in civic affairs. He is the author of A Negro on Mormonism.66 One of the outstanding Black writers of the 1920s and early 1930s, Wallace Thurman, was born in Salt Lake City. He wrote two novels, The Blacker the Berry and Infants of the Spring, two plays, and was a ghostwriter for a magazine. Because of his dedication to art and excellence, Thurman was critical of Black writers who did not strive for perfection. He died in 1934 at the age of thirty-two.67

It is in discrimination against Utah Blacks that their history here becomes a microcosm of Black history in the United States. The age-old attitude of white superiority and Black inferiority continues to prevail. With immigrants from the Balkans and the Mediterranean initial discrimination was strong but of relatively short duration and never so virulent as that experienced by Blacks. Public opinion kept the new immigrants out of certain areas in towns and cities and frowned on intermarriage, but laws restricted Blacks in housing and public accommodations and through the Anti-Miscegenation Law (1898?1963) prohibited marriage with whites.68

One of the paradoxes of Black-white relationships lies in the entertainment field: whites flocked to hear Black artists but would not allow them rooms in their hotels or service in their restaurants. Local Blacks faced the ignominy of having to sit in the balcony sections of theatres and stand outside the ballrooms of Lagoon, Saltair, and the Rainbow Gardens to hear the music of their fellow Blacks.69

Before World War II, a French Black singer, Lillian Yvanti, stayed with the Frank Johnsons while in Salt Lake City because she was denied rooms in leading hotels in town. During the 1940s and 1950s similar incidents continued. Marian Anderson, famed concert singer, was allowed to stay at Hotel Utah on condition that she used the freight elevator. Harry Belafonte was also refused rooms at Hotel Utah but was accepted at the Hotel Newhouse which had previously barred Blacks. Ella Fitzgerald and her entourage were placed in a Black hotel on the west side of Salt Lake City because no white hotel would take them. To avoid embarrassment, pianist Lionel Hampton’s wife used the ploy of asking local sponsors to find a hotel for them that would take her two small dogs.70 This discrimination against nationally known entertainers occurred frequently in other parts of the United States as well as in the South.

The breakthrough in Utah was the result of the determined efforts of Robert E. Freed, a prominent leader in civil rights. When the Freed family and their partner, Ranch Kimball, took over the lease of Lagoon, the terms forbade Blacks in the swimming pool and the ballroom in accordance with a Farmington town ordinance. By the late 1940s, Robert Freed had succeeded in fully opening Lagoon to Blacks; and when his company acquired the Rainbow Gardens (Terrace), the same policy was adopted. The NAACP Fifty-sixth Annual Membership and Freedom Banquet Program on April 25, 1975, honored Freed posthumously.71 Providing entertainers with first-class accommodations had to wait until the state and federal legislation of the 1960s.

Overt discrimination against Blacks has ranged from lynchings to rejections in housing, public accommodations, and employment.72 In 1869 a Black was shot and hanged at Uintah in Weber County. The reason given was “he is a damned Nigger.”73 In 1925 Robert Marshall was taken from his jail cell in Price by a mob and hanged “in slow stages.” The rope was pulled until he lost consciousness; he was then revived by burning his bare soles with matches. The pulling and burning continued until Marshall died to the cheers of men, women, and children who smiled for a photographer while the dead Black swung from the hanging tree in the background. Law officers arrived unaccountably late.74

Lynching was the extreme form of discrimination and housing difficulties the common form. In 1939 Salt Lake City commissioners received a petition with one thousand signatures asking that Blacks living in Salt Lake be restricted to one residential area. This area would be located away from the City and County Building where visitors to the city would not come in contact with a sizeable number of Blacks. The petition was initiated by Sheldon Brewster, a realtor and bishop of a Mormon ward.75 Brewster employed a local Black in the attempt to persuade Blacks to sell their houses and agree to be colonized in one location, but he failed to secure their cooperation. Blacks rose up in indignation and marched to the Capitol to protest Brewster’s action.76 When the petition failed to get the approval of the commissioners, a restrictive covenant policy was used to limit Black opportunities in housing. Real estate companies inserted a Form 30 clause in real estate contracts:

The buyer, his heirs, executors, administrators, successors, or assigns agree that no estate in possession of the said premises shall be sold, transferred granted, or conveyed to any person not of the Caucasian race.

Although restrictive clauses were ruled unconstitutional in 1948, many deeds continued to include them.

Typical statements from whites on the issue of Blacks and housing are:

A Negro is all right in his place, but his place is down below you. You can’t treat them as an equal or they will take advantage of you every time. You have to keep them down. Yet, the property around here isn’t worth as much since they moved on the block, but I guess they have to have some place to live. I understand there is some kind of a city ordinance against selling to them, but it hasn’t kept them out of here.

I don’t like them around here but there is nothing you can do about it. One thing, they train their dogs and kids right. They are a lot better mannered than the white kids in the neighborhood. Once in a while you see a drunk Nigger, but he is no worse than a drunk white man. But those that are good, you can bet that it is the white blood they got in them.77

Even with the protection of recent federal law, Blacks still have problems in renting or purchasing homes.78

In the area of public accommodations, more specifically hotels, restaurants, and social organizations, Blacks have suffered the indignity of being refused admittance or service. In instances where a Black was accommodated, he sometimes would have to accept second-class treatment. As in housing, Blacks are often confronted with discrimination in public accommodations despite federal law.79

Employment opportunities, while somewhat improved for Blacks (largely because of federal law), nevertheless continue to be limited, specifically in the area of job-advancement opportunities. While many employers have made meaningful attempts to guarantee equal employment opportunities, others have sought merely to stay within the limits of the law. As a result tokenism is common when it comes to Blacks in visible positions. Even where progress has been more or less a token gesture, it is the result of a long, hard struggle. Mignon Richmond, who was graduated from Utah State Agricultural College (now Utah State University) in 1921, was unable to find work as a teacher and for many years worked as a laboratory technician and school lunch supervisor. Mrs. Richmond has given many years of active service to both the NAACP and the YWCA.80

There are two branches of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Utah. The Salt Lake City group was organized in February 1919, ten years after the founding of the national body. The Ogden branch was organized in 1943. Despite limited membership and funds, both branches have been active in the struggle for human rights. In addition to the NAACP, there have been several other organizations such as B’nai Brith, the Japanese-American Civic League, and the Urban League that have worked to bring rights to all people.81

In Utah the Mormon church’s denial of its priesthood to Black men has hampered their fight for human dignity. Blacks see it as a hindrance to gaining full rights in that they cannot be held in equal esteem with others because denial implies inferiority. The LDS church maintains that it is possible to support civil rights and preserve existing religious opinion. The assertion that denial of priesthood to Blacks is a theological position with no sociopolitical relevance is a specious dichotomy to Blacks.82

Nevertheless, Blacks have joined the Mormon church. It has been suggested that their roots in fundamentalism made them amenable to accepting the doctrines of LDS theology and that the self-sufficiency, unity, and independence from outside institutions, advocated by fundamentalist religions and mirrored in the Mormon church, further increase its appeal for Black converts.

Blacks have lived in Utah for more than a century and a quarter and in the United States for more than three and a half centuries. During these years progress has been limited to individuals and not to the race as a whole. In considering the historical experience of Blacks in Utah and the United States, encompassing the struggle from slavery and the continuing quest for human rights, one is reminded of words uttered by a female slave of the nineteenth century: “Oh, Lord Jesus, how long, how long?”83

1James P. Beckwourth, The Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, ed. Thomas Banner; new introduction and epilogue by D. R. Oswald (Lincoln, Nebr., 1972), introduction, vii-xiii, pp. 541-43.

2 Ibid., p. 628

3 The Expeditions of John Charles Fremont, ed. Donald Jackson and Mary Lee Spence, 2 vols. (Chicago, 1970) 1: 383, 388, 427-28.

4 Interview with Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead, August 1974.

5 Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saints Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City, 1901-36), 4:703. The names are listed separately from other pioneers and appear under the heading “colored servants.” The three men were slaves of southern converts to the LDS church.

6 1850 Census.

7 Ibid. Microfilm copies of the holograph schedules are available at Marriott Library, University of Utah, and Utah State Historical Society, both in Salt Lake City.

8 1860 Census.

9 “An Act in Relation to Service” in Utah Territory, Legislative Assembly, Acts Resolutions and Memorials (Salt Lake City, 1852), pp. 80-82.

10 Alfred H. Kelley and Winfred A. Harbison, The American Constitution: Its Origins and Development (New York, 1970), p. 433.

11 Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City, 1965), pp. 17-26.

12 Ibid., pp. 47-48.

13 O. D. Flake, William J. Flake, Pioneer-Colonizer (Salt Lake City, 1948), pp. 10-11.

14 A comparison of the Utah census schedules of 1850 and 1860 indicates that several of the Blacks listed as free in the 1850 Census were slaves and that the slaves living in Bountiful, Utah, were not included in the census.

15 Andrew L. Neff, History of Utah: 1847-1869, ed. Leland H. Creer (Salt Lake City, 1940), p. 219; 1850 Census.

16 Eugene Brewer, The Frontier Against Slavery; Western Anti-Negro Prejudice and the Slavery Extension Controversy (Urbana, Ill., 1967), p. 65.

17 Flake, William J. Flake, pp. 3-12.

18 “Pioneers of 1847–A Collective Narrative,” manuscript, Archives Division, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. This narrative was compiled from several pioneer Journals.

19 Carter, Negro Pioneer, pp. 5-7.

20 Henry J. Wolfinger, “A Test of Faith: Jane Elizabeth James and the Origin of the Utah Black Community,” research paper, 1972, pp. 2-7, 19-22, LDS Archives.

21 Carter, Negro Pioneers, pp. 9-13.

22 Wolfinger, “Jane Elizabeth James,” p. 5.

23 Frank Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1913), p. 85.

24 Wolfinger, “Jane Elizabeth James,” pp. 6-9, 10; Carter, Negro Pioneer, p.11.

25 Lester E. Bush Jr., “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8 (1973) : 16-17. Jenson, Biographical Encyclopedia, 3:577. Notes taken from Elijah Abel File, LDS Archives.

26 “Pioneer Emigrants From Europe,” microfilm, LDS Archives; 1870 Census.

27 “An Act in Relation to Service,” pp. 80-82.

28 “A Preamble and an Act for the Further Relief of Indian Slaves and Prisoners,” in Acts, Resolutions, and Memorials, pp. 93-95.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid., pp. 82, 94.

31 Broad Ax, March 25, 1899. Alexander and Marinda Bankhead, former slaves, were interviewed by Julius Taylor, owner and publisher of the Broad Ax, a Black newspaper.

32 Carter, The Negro Pioneer, pp. 25-26.

33 Broad Ax, March 25, 1899.

34 Carter, The Negro Pioneer, pp. 42-43.

35 Dennis L. Lythgoe, “Negro Slavery in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly 39(1971): 41-42.

36 Broad Ax, March 25, 1899. The city and county building referred to was the old City Hall located on First South near State Street.

37 Charles W. Nibley, Reminiscences: 1849-1931 (Salt Lake City, 1934), pp. 35-36.

38 Wolfinger, “Jane Elizabeth James,” pp. 12-15.

39 Charles Kelly, The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch, rev. ed. (New York, 1959), pp. 320-22.

40 William Loren Katz, The Black West: A Documentary and Pictorial History, rev. ed. (Garden City, N.Y., 1973), p. 158.

41 Philip Durham and Everett L. Jones, The Negro Cowboys (New York, 1965), pp. 185-86.

42 Ibid., pp. 203-5; Byrdie Howell Langon, Utah and the Early Black Settlers (Los Angeles, 1969), pp. 31-32.

43 Jack D. Foner, Blacks and the Military in American History (New York, 1974), pp. 52-55.

44 Michael J. Clark, “A History of the Twenty-fourth United States Infantry Regiment 1896-1899” research paper, University of Utah History Department, 1974, p. 12.

45 Durham and Jones, Negro Cowboys, p. 10.

46 Thomas G. Alexander and Leonard J. Arrington, “The Utah Military Frontier, 1872-1912, Forts Cameron, Thornburgh and Duchesne,” Utah Historical Quarterly 32 (1964): 344-52.

47 Clark, “The Twenty-fourth Infantry,” pp. 14-16, 19, 21.

48 Foner, Blacks and the Military, pp. 70-7 1.

49 Clark, “The Twenty-fourth Infantry,” pp. 22, 25, 33-35.

50 Carter, The Negro Pioneer, pp. 7 1-73.

51 George Ramjoue, “The Negro In Utah: A Geographical Study in Population” (M.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1968), pp. 19?21, 71?73.

52 Interviews with Fantley Jones, February 1974, and William Gregory, August 1974. Mr. Gregory arrived in Salt Lake City in 1913. He worked as a Pullman porter for over forty years.

53 Jones interview.

54 Ibid.

55 Interview with Nick Papanikolas, March 12, 1975, who recalled this information from a previous talk with Lee Brown, Denver and Rio Grande Western ballplayer of the 1920s, and Claude Engberg, president of the Pioneer Baseball League for many years.

56 Wolfinger, “Jane Elizabeth James,” p. 15. Interview with Rev. Frances Davis, minister of Calvary Baptist Church, December 1974, Salt Lake City.

57 J. Cecil Alter, Early Utah Journalism (Salt Lake City, 1938), pp. 274, 330, 390.

58 Broad Ax, September 14, 1895. The majority of Blacks in the United States during this period supported the Republican Party. The party of Abraham Lincoln had ended slavery and made an issue of Black rights during Reconstruction.

59 Broad Ax, September 14, 1895.

60 Ibid., November 20, 1897.

61 Ibid., July 25, 1896.

62 Interview with Mary Lucille Perkins Bankhead.

63 Ibid.; interview with William Gregory.

64 Edward “Duke” Ellington, Music Is My Mistress (Garden City, N.Y., 1973), pp. 49?50.

65 Interview with Officer Jake Green, Salt Lake City Police Department, February 1974; Langon, Utah and the Early Black Settlers.

66 Gregory interview.

67 Nathaniel Irvin Huggins, Harlem Renaissance (London, 1973), pp. 191?95 239?43.

68 Margaret Judy Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro and Institutional Efforts to Eliminate It” (M.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1971), pp.87-88.

69 Wallace R. Bennett, “The Legal Status of the Negro in Utah,” Symposium on the Negro in Utah, Utah Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, Weber College, 1954.

70 Harmond O. Cole “Status of the Negro in Utah,” Symposium on the Negro in Utah, p. 1. Interview, May 5, 1975, with Peggy Johnson Clark; interview May 5, 1975, with Peter Freed, president of Lagoon.

71 See Salt Lake Tribune, July 18, 1974, for Robert E. Freed obituary and Deseret News, July 18, 1974, for obituary and July 19, 1974, for editorial.

In earlier years Lagoon had closed to the “public” after Labor Day. Then, on one day following the holiday, Black families were allowed to use the resort facilities before they were shut down for the winter.

72 Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro,” pp. 29-3 1.

73 Robert G. Athearn, Union Pacific Country (Chicago, 1971), p. 87.

74 News Advocate (Price),June 18, 1925.

75 Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro,” pp. 45-47.

76 Bankhead interview.

77 Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro,” pp. 47-48.

78 This writer has personal knowledge of Blacks in Salt Lake City who have been refused housing because of their color. Professor Shelby Steele, a former member of the University of Utah faculty, and Professor Raymond Horton, a former graduate student at the University of Utah, filed suits against individuals who denied them housing because of their race.

79 Interview with Grady Farley, former graduate student, University of Utah, fall 1973. There are some nightclubs in Salt Lake City that have refused to permit a Black to enter, even though the Black person possessed a membership card.

80 Maag, “Discrimination Against the Negro,” pp. 40-41.

81 Ibid., pp. 63-73.

82 Bush, “Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine,” 44-45, 67. This article is the most comprehensive study to date on the subject.

83 Leslie H. Fishel, Jr., and Benjamin Quarles, eds., The Black American: A Documentary History, rev. ed. (Glenview, Ill., 1970), pp. 86-87. 140.