Michael W. Johnson

History of Daggett County

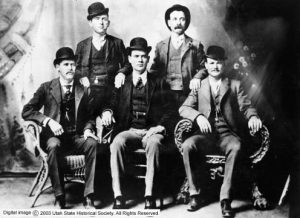

Butch Cassidy (right) and his gang in 1900

While Browns Park ranchers fought the wealthy for control of the range, there were others who took the battle a step farther. Men like Butch Cassidy, Elza Lay, Harry Longabaugh (the Sundance Kid), and Matt Warner became bandits, robbing banks and trains and giving at least some of the money to the poor. In terms of background and values, they were not much different from the besieged ranch folk. Cassidy, Lay, and Warner had all cowboyed in Browns Park before becoming professional outlaws. Caught up in their own war with rich neighbors, it is no wonder that people in Browns Park found common cause with these outlaws and provided them a haven.

Sometimes called the “Wild Bunch,” this loose aggregation of criminals plied their trade throughout the Mountain West from three remote bases: the Hole-in-the-Wall country of Wyoming, the Robbers’ Roost area of central Utah, and Browns Park. All were isolated and difficult for the law to penetrate. When things got too hot in one location, the outlaws just headed down the Outlaw Trail to another hideout.

Wherever they stayed, Butch Cassidy and his cohorts made it a point to get along. Cassidy had a genial manner that enabled him to make friends easily, and he tried to avoid violence. When he needed a meal or a horse, he always paid for it. More importantly, he and his group actively aided the poor. In part, this was a shrewd strategy that helped ensure aid and shelter from the community; but it also was motivated by a sense of altruism. Giving made the outlaws feel good and, in their minds, justified a life of crime. One gang member wrote: “Like lots of cowboy outlaws in them days Butch and me liked to give lots of money to the poor, the needy, and the deserving. In this way we made sort of Robin Hoods of ourselves in our own eyes, gained a lot of popularity and protection from the public, and squared ourselves in our own estimation.”

Two incidents stand out as demonstrations of the outlaws’ affection for the people of Browns Park. On one occasion, Matt Warner, Elza Lay, and two others held up a merchant who was freighting a load of merchandise from Rock Springs to Vernal. After taking what they could use, the robbers determined to donate the balance of the goods to their neighbors. Clothes and trinkets were given to storekeeper John Jarvie for distribution, and everyone was told to show off their new apparel at the next dance. When Friday night rolled around, some of the dancers sported rather outlandish ensembles.

An even more fanciful event took place in the middle 1890s when the Bender Gang, Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid, and Elza Lay treated the residents of the valley to Thanksgiving dinner. No expense was spared. The menu included blue point cocktails, roast turkey with chestnut dressing, cranberries, Roquefort cheese, pumpkin pie, and many other delicacies. Held at the Davenport ranch, the affair attracted some thirty-five people. Isom Dart presided in the kitchen, and the outlaws donned white aprons to serve dinner. Ann Bassett recalled that Butch Cassidy got flustered pouring coffee and retreated from the dining room. “The boys went into a hud[d]le in the kitchen and instructed Butch in the formal art of filling cups at the table. This just shows how etiquette can put fear into a brave man’s heart.”

When these Robin Hood bandits were not robbing banks or throwing parties, they often caroused in an old cabin on Charley Crouse’s place. Drinking and poker were the favorite pastimes, and local residents could be trusted to send warning if law officers were nearby.

By the dawn of the twentieth century, law officers were nearby a good share of the time. It became more and more difficult to elude the relentless pursuit of sheriffs and private detectives, and many of the Wild Bunch were apprehended and sentenced to prison. Hoping to avoid that fate, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid left the country for Bolivia in 1902. Conventional wisdom holds that they were killed there in a shoot-out with law officers, but unsubstantiated reports persist that Cassidy returned to the United States and finished out his years in peaceful obscurity. Whatever the case, the long arm of the law had proved that it could now reach into the most remote corners of the West. The glory days of the Outlaw Trail were over.