Thomas G. Alexander

Utah, The Right Place

By the early 1840s, as immigrants struck out for Oregon and California, Americans contemplated adding both of these regions as United States possessions. Enthusiasts such as Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton, his daughter Jessie, and her husband, John C. Fremont, considered an empire on the Pacific as America’s “Manifest Destiny.” Judging themselves agents of God’s plan, they set about gathering and publishing information about the Far West.

Trained as a topographical engineer, Fremont possessed an expertise unprecedented in western exploration. Anxious to excite other Americans with his family’s vision, he hoped to promote settlement and acquisition by the United States. To accomplish that aim, Jessie helped in writing and editing, and his father-in-law facilitated the publication of his reports.

Three of Fremont’s five expeditions took him into Utah, but the 1843-44 expedition undoubtedly had the greatest impact. Officially, Col. John Abert of the United States Topographical Engineers sent Captain Fremont to link surveys of the western interior with the Pacific slope explorations of Lt. Charles Wilkes. Guided by Thomas Fitzpatrick and Kit Carson and including trained technicians such as cartographer Charles Preuss among the thirty-odd members of his expedition, Fremont dispelled some myths, but most important, he stirred the imagination of an enraptured, land-hungry public.

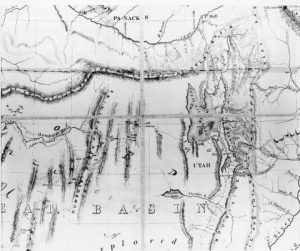

The 1843 expedition took him from St. Louis to Soda Springs and then down the Bear River through Cache Valley to the Great Salt Lake. As Fremont traveled these valleys with his party, he wrote glowing descriptions of the soil, vegetation, and animals, touting the valleys as location for future settlement. Paddling a leaky rubber boat to Fremont Island—he called it Disappointment Island—the explorer and his party mapped the lake; reported on its mineral content, flora, and fauna; and, using barometric and boiling-temperature readings, estimated its elevation at 4,200 feet above sea level. From the Great Salt Lake, the party traveled northwestward to the Oregon Trail, on to Fort Vancouver, and then southward, mapping the western edge of the Great Basin.

Fremont, known as the Pathmarker, firmly established a number of geographic conceptions. Although Bonneville had published maps based on Walker’s explorations showing that the Great Salt Lake has no outlet to the Pacific Ocean, Miera’s Rio de San Buenaventura continued to dominate popular lore. Fremont’s explorations finally laid Miera’s supposition to rest. He also proved that the Sierra Nevada and Cascade ranges formed a continuous chain and firmly established the concept of the Great Basin as an enclosed interior bowl.

Charles Preuss map of 1848. Preuss was cartographer for John Charles Fremont. Library of Congress photo.

Crossing the Sierra Nevada to California, Fremont traveled south in California and returned to Utah Lake by way of the Old Spanish Trail, Mountain Meadows, and the Dominguez-Escalante/Jedediah Smith route. On his return, he met Joseph R. Walker. Guided by the Mountain Man, he turned east up Spanish Fork Canyon. His party stopped at Forts Robidoux and Davy Crockett before returning to the Midwest.

Fremont’s 1845 exploration took him again to the Great Salt Lake and to California. This time, he entered Utah by way of the White River and the Unita Basin, crossing to the upper reaches of the Provo River. Following the Provo to Utah Lake, he traced the Jordan River to the Great Salt Lake. After camping on the site of Salt Lake City, Fremont and his party spent two weeks exploring the lake, crossing to Antelope Island in the process. After killing several antelope on the island, Fremont encountered an old Ute who claimed ownership of the game, and Fremont gave him some trade goods for the animals. From the southern edge of the Great Salt Lake, Fremont blazed a trail across the Great Salt Lake Desert (the Hastings Cutoff would later follow this route). Reaching Pilot Peak and the Humboldt River, both named by Fremont, he divided his party before pressing on to California and Sutter’s Fort.

Fremont again came to Utah in 1853 in a futile attempt to find a feasible transcontinental railroad route. The winter crossing of the High Plateaus proved extremely arduous, leaving the entire expedition in desperate straits before they reached the Mormon settlement at Parowan.

In the process, Fremont made some geographical and judgmental mistakes. In spite of the fact that Utah Lake held fresh water, he labeled it a southern arm of the Great Salt Lake. This geographical mistake precipitated a controversy with Brigham Young. Also, Fremont’s judgmental mistake in crossing the Rockies, the High Plateaus, and the Sierra Nevada in the winter caused several deaths in his party.

Nevertheless, Fremont’s explorations proved enormously successful. Charles Preuss’s maps far outshone anything previously available. Fremont’s descriptions, ably romanticized by Jessie Benton to catch the public imagination, publicized the region and enthused numerous travelers, including the Mormons, about the country. The names he gave to some physical features such as Pilot Peak and the Humboldt River replaced their previous labels, and scientist named a number of hitherto uncatalogued animals and trees in his honor.

It is difficult to overstate the influence of the 1843–44 expedition. Sections of Fremont’s report found their way into Joseph E. Ware’s The Emigrant Guide to California; Josiah and Sarah Royce used the Pathmarker’s Travels to find their way to California; lectures at the Royal Geographical Society in London summarized his work; and Mormon leaders in Nauvoo read it avidly. Alexander von Humboldt praised Fremont’s “talent, courage, industry, and enterprise.”