View of the Gardo House from the northeast in the 1870s, while it was still under construction. Note the scaffolding on the tower and the empty window openings awaiting the installation of window sashes. The picket fence seen here was later replaced with wrought iron.

On November 26, 1921, a crowd gathered at 70 E. South Temple Street in downtown Salt Lake City to watch the demolition of a Victorian mansion. One onlooker was ninety-year-old John Brown. In spite of the November chill and the fact that it was his birthday, Brown had come to pay his last respects to the doomed building; he had been the construction foreman for the house when it was built almost fifty years before. But even for those Utahns without personal ties, the place was special. The building being demolished was the Gardo House.1

The Gardo House, also known as Amelia’s Palace, has been an object of great curiosity and controversy. At one time the mansion was heralded as one of the finest homes between Chicago and the West Coast. But, no less than its unusual architecture and legendary interior, the people associated with it have been an integral part of the home’s distinctive reputation.

The home had its beginning when, during the last years of his life, Brigham Young, president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon church) perceived a need for a place where he could receive official callers and entertain the dignitaries who traveled great distances to see him. He selected a lot on the corner directly south of his Beehive House and began construction in 1873. The Mormon prophet was fond of naming his homes, and one source claims that he borrowed the name Gardo from a favorite Spanish novel.2

Joseph Ridges, designer and builder of the Tabernacle organ on Temple Square, and William Harrison Folsom, Young’s father-in-law, worked together to draw the plans and superintend the construction. Folsom, who had been LDS Church Architect from 1861 to 1867, had played a vital role in the design and construction of the Salt Lake Theatre, Salt Lake Tabernacle, St. George Tabernacle, Salt Lake Temple, Manti Temple, St. George Temple, and many private residences.3

There were widespread rumors that the Gardo House was being built for Folsom’s daughter, Harriet Amelia Folsom Young, who was allegedly Brigham Young’s favorite wife. It was indeed Young’s intent that Amelia would serve there as his official hostess. According to his daughter Susa Young Gates, family members agreed that Amelia, who was young, childless, refined, and talented, was the ideal wife to assume such large social responsibilities.4

Brigham Young and his wife Amelia Folsom Young in what is probably a composite photo. Gossip about this “favorite wife” has fueled popular interest in the Gardo House.

Amelia had first become acquainted with President Young on October 3, 1860, when he welcomed the Folsoms’ wagon company to Salt Lake City. Tall and graceful, with blue eyes and light brown hair, Amelia was intelligent and charming. She was also an accomplished pianist and vocalist. Young began courting her almost immediately; they married on January 24, 1863.5

Progress on the mansion was slow. There were numerous delays in obtaining the necessary lumber, plaster, granite, and glass.6 President Young, who was often away on church business, was seldom available to sign requisitions or make important decisions. However, on one occasion, after returning to Salt Lake City from a visit to St. George, he expressed displeasure with the style of the home, calling it his “tabernacle organ.”7

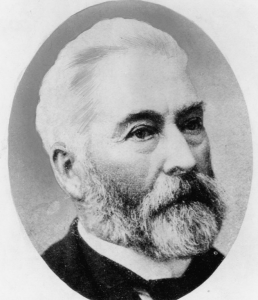

William H. Folsom, one of the designers of the Gardo House, was the father of Amelia Folsom Young, for whom the house was nicknamed “Amelia’s Palace.”

After three years of construction, the Gardo House was nearing completion when an unfortunate accident occurred near Arsenal Hill (now Capitol Hill), a repository for gunpowder and explosives. On April 5, 1876, two young hunters fired their guns into one of the powder magazines. The resulting explosion showered the city with 500 tons of boulders, concrete, and pebbles. Many persons were injured; some, including the hunters, were killed.8 The explosion also broke several of the glass windows in the Gardo House, and new glass had to be ordered from the East. By May 20 the windows were reinstalled and construction had resumed.9

Brigham Young never lived to see the completed mansion; he died on August 29, 1877. The settlement of Young’s estate was divided into three parts: church properties in Young’s name, properties belonging to his private estate, and properties where legal ownership was unknown. In his will, Young had provided both Mary Ann Angell Young and Harriet Amelia Folsom Young a life tenancy in the Gardo House, and in order to secure their claims, the two women occupied the mansion briefly while it was still under construction. Although the legal ownership of the mansion was in question, the settlement credited it to Young’s heirs instead of to the church, at the highly inflated figure of $120,000. Of this sum, approximately $20,000 was paid to Mary Ann Angell Young and Harriet Amelia Folsom Young.10

Although John Taylor was undoubtedly the most influential man in the territory, he was uncomfortable with the opulent image his occupancy of the Gardo House portrayed.

John Taylor succeeded Young as church president. His counselor George Q. Cannon and other church leaders suggested that Taylor occupy the Gardo House after its completion, but he repeatedly refused. However, when church members unanimously voted on April 9, 1879, to make the Gardo House the official parsonage for LDS church presidents, President Taylor reluctantly accepted their decision.11

Moses Thatcher, William Jennings, and Angus M. Cannon were appointed as a committee to oversee completion of the mansion.12 The finished home had four levels, including the basement, with a tower on the northwest corner. The foundation and basement were made of granite. The exterior walls were of 2 x 6 studs infilled with adobe bricks, with lath and plaster on the inside and two layers of lath and stucco on the outside. The interior woodwork, which included a spiral staircase, paneling, and decorative trim, was carved in black walnut by local artists. Elegant furnishings, paintings by local artists, and mirrors imported from Europe graced all the rooms.13

On December 27, 1881, the Deseret News published a letter from John Taylor announcing a public reception and tour of the Gardo House on January 2, 1882, from 11 a.m. until 3 p.m. More than two thousand people attended the reception and toured the home. President Taylor greeted all the visitors, who were entertained by two bands and several renditions by the Tabernacle Choir. A year later, on February 22, 1883, the mansion was dedicated as a “House unto the Lord” in a dedicatory prayer offered by Apostle Franklin D. Richards.14

John Taylor’s move to the Gardo House was regarded by Mormons as the fulfillment of a prophecy. Legend had it that some years before, when Taylor’s financial circumstances had been the poorest, Heber C. Kimball had boldly prophesied that Taylor would someday live in the largest and finest mansion in Salt Lake City.15 But there were some Mormons and many non-Mormons who were not pleased with the reception or with Taylor’s occupancy of the home. Rachel Emma Woolley Simmons recorded in her journal:

Brother John Taylor gives a reception in the Gardo House. . . . I have no fault to find with him for moving into that house, but I think it would have been more becoming if he had stayed in his own home. It was a great expense to furnish it in the style it had to be. . . . I don’t believe he is enjoying it much. I heard that his wives were not pleased with the move.16

The Salt Lake Daily Tribune was extremely critical of the affair and of the church in general. In an editorial published the day before the reception, the newspaper wrote,

The favored saints have received an invitation to call upon President John Taylor at the Amelia Palace tomorrow. . . . We want the poor Mormons . . . to mark the carpets, mirrors, the curtains and the rest, and then to go home and look at the squalor of their own homes, their unkempt wives, their miserable children growing up in despair and ignorance, and then to reflect how much better it would have been for them, instead of working hard for wages . . . if they had only started out as did Uncle John, determined to serve God for nothing but hash.

The Tribune went on to accuse the church of attempting “to build up an aristocracy in Utah, where the few are to rule in luxury, while the many, to support the luxury, are to toil and suffer.”17

On January 5, 1882, the Deseret News published a rebuttal to the Tribune’s scathing editorial. The newspaper pointed out that Taylor had taken up his residence in the Gardo House in response to the vote of the Mormon people and that he, as church president, should

. . . be at least as well housed and cared for as prominent men in Church or State here or elsewhere. . . .We are pleased to see that one of the veterans of the latter-day work, who has traveled from land to land and from sea to sea, who has suffered with the exiles and bled with the martyrs, forsaken all things for the truth . . . is now surrounded with comfort, and has a place to lay his head and to receive his friends.

Taylor himself also wrote a letter, published in the Deseret News, expressing his feelings about the situation. He reminded critics of his initial reluctance to move to the Gardo House and his concern that his occupancy of the mansion would place an intolerable barrier between him and church members. Taylor acknowledged that his family had also been opposed to the move, preferring their own homes and familiar surroundings. He explained he had eventually been persuaded that

Zion should become the praise of the whole earth, and that we in this land should take a prominent and leading part in the arts, sciences, architecture, literature, and in everything that would tend to . . . exalt and ennoble Zion. [It is the president’s duty] to take the lead in everything that is calculated to . . . place Zion where she ought to be, first and foremost among the peoples.18

The Drawing Room (or Main Parlor), looking toward the Music Room.

Both newspapers were correct in implying that the issue of the Gardo House was much broader than the mere occupation of the mansion by a Mormon leader. To Mormons, who had celebrated their church’s jubilee in April 1880, the house was a symbol of achievement. It was tangible proof that the persecutions and hardships they had endured over the past fifty years were not in vain.19 On the other hand, many non-Mormons viewed Taylor’s installation in the home as a threat in the continuing struggle for economic and political supremacy.

In 1882 another important event intensified suspicions and ill feelings between Mormons and non-Mormons. In March that year, Congress passed the Edmunds Act, which made polygamy a felony punishable by up to five years in prison and/or a $500 fine. It also disfranchised polygamists and declared them ineligible for jury duty or public office.20 In response, John Taylor held a meeting in the Gardo House with sixteen general authorities of the church to discuss the Edmunds law and its threat to their religious practices and to statehood. According to Wilford Woodruff, “President Taylor with the rest of us came to the conclusion that we could not swap off the Kingdom of God or any of its Laws or Principles for a state government.”21

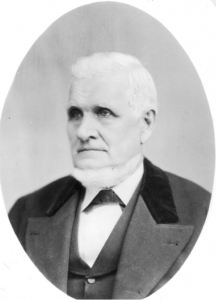

LDS church president Wilford Woodruff and his counselors, George Q. Cannon and Joseph F. Smith. During Woodruff’s administration he used the Gardo House as his office and paid the federal government rent to do so.

Despite these pressures, the polygamous Mormon leader endeavored to conduct church business as usual within the Gardo House. Every morning at 8:30 George Reynolds, secretary to the LDS First Presidency, reported for work at the mansion. Reynolds recorded at least two important revelations that Taylor received in the Gardo House. However, President Taylor eventually decided to make outward appearances conform as much as possible to the requirements of the anti-polygamy laws. He told his wives, ” . . . under the circumstances it will be better for me or for you to leave this place; you can take your choice.” Taylor’s wives opted to return to their own homes, and his sister, Agnes Schwartz, became matron of the home.22

Mormons began to feel the teeth of the Edmunds Act when federal officers arrived in Utah to replace existing lawmen and enforce the new law. Federal marshals made raids on Mormon households, searching for lawbreakers and witnesses.

The Gardo House served as one meeting and hiding place for those fleeing from federal marshals. According to John Whitaker, son-in-law of John Taylor,

The Gardo House was a rendezvous where the brethren and sisters on the underground would often come in the night to meet their loved ones. . . . Samuel Sudbury, a mysterious man, was custodian of the Gardo House and was ever on the alert for the approach of marshals and deputies searching for polygamists. It was the rule that the Gardo House was to be closed at 10 p.m. without exception, and no stranger was permitted after that hour.23

Church leaders were considered prime catches by federal lawmen. Taylor’s homes, the church offices, and the Gardo House were always under the surveillance of spies and deputy marshals. As persecution mounted, President Taylor decided to go “underground”–into hiding. His last public appearance was in the Salt Lake Tabernacle on February 1, 1885.24 A few weeks later, on March 13, marshals made a massive raid on the Gardo House to capture Taylor. The raid was unsuccessful, but other raids soon followed. Taylor’s tough-minded sister, Agnes Schwartz, often held raiding marshals and deputies at bay at the front door of the mansion, admitting no one unless he presented papers properly signed by a federal judge.25

On one occasion, deputies searched the house for Charles W. Penrose, editor of the Deseret News, who was hiding under the name of Dr. Williams. The deputies combed the house from top to bottom but could not find Penrose, who was concealed in a specially built closet on the top floor. At one point, the lawmen stood within a foot of him. Penrose later recalled, “I had such a cold and wanted to cough so badly I held my breath until I almost burst, and was thankful Mr. Frank Dyer, the U. S. Marshal, left so I could relieve myself coughing. “26

On November 1, 1886, John Taylor’s family assembled in the Gardo House to celebrate his seventy-eighth birthday. Taylor, who remained in hiding, dared not attend but sent a letter expressing love and concern for his wives and children. He deeply mourned that he was unable to comfort two of his wives, Jane and Sophia, who were dangerously ill. Taylor closed his letter, “Some of you have written that you ‘would like to have a peep at me.’ I heartily reciprocate that feeling, and would like to have a ‘peep’ at you on this occasion, but in my bodily absence my spirit and peace shall be with you.”27

On February 19, 1887, church leaders’ worst fears were realized when Congress passed the Edmunds-Tucker Act. The new law dissolved the Corporation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, abolished woman suffrage in the territory, disinherited children of plural marriages, took control of Utah’s Mormon-dominated public schools, dissolved the Perpetual Emigrating Company, abolished the territorial militia, and confiscated virtually all church property. The crusade against polygamy took a heavy toll on the church and its followers. John Taylor died while still in hiding, in Kaysville, Utah, on July 25, 1887. On July 28 Wilford Woodruff and others went to the Gardo House to view Taylor’s remains, which were lying in state at the mansion. The next morning at 6 a.m. the Taylor family assembled at the Gardo House to pay their last respects before his body was removed to the Tabernacle for the funeral.28

The day after the funeral, the United States District Attorney for Utah brought a lawsuit against the church to enforce the escheatment provisions of the Edmunds-Tucker Act. The court appointed Frank H. Dyer, United States Marshal, as receiver to hold and administer church property. Dyer seized the general tithing office, the Gardo House, the church historian’s office, and other church properties such as buildings, farms, mines, livestock, and stock in various corporations. The Mormons were forced to pay the government high rental fees to retain the use of their property. Rent for the Gardo House was initially set at $75 per month but later skyrocketed to $450 per month.29

Wilford Woodruff succeeded John Taylor as fourth president of the church. He kept an office in the Gardo House, where he frequently held public and private gatherings and occasionally spent the night. The new prophet spent part of each day at the Gardo House attending to correspondence, conducting interviews, and signing temple recommends. On Thursdays and Saturdays the First Presidency and other church leaders held prayer meetings in the mansion. They also met regularly to discuss the completion of the Salt Lake Temple, the operation of Zions Cooperative Mercantile Institution (ZCMI), the selection of delegates to Congress, and the ordination of new apostles.30

In August and September of 1890, Wilford Woodruff took a 2,400-mile journey to visit the principal Mormon settlements throughout Wyoming, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. After returning home for a brief stay, he traveled to San Francisco, where he met with business and political leaders Isaac Trumbo, Judge Morrill Estee, Senator Leland Stanford, and Henry Biglow. He returned to Salt Lake City convinced by what he had seen and heard that the very existence of the church was in jeopardy. The government was threatening to confiscate church temples, halting all ordinances for the living and dead; to imprison the First Presidency and Twelve Apostles; and to confiscate the personal property of the saints. The beleaguered prophet arrived at the conclusion that he must act for the temporal salvation of the church by advising members not to enter into plural marriages. Woodruff sought and received divine confirmation of this decision on September 23, 1890. The next day, his counselors and the apostles sustained the revelation and drafted what would become known as the Manifesto.31

On October 5, 1890, church leaders held a special meeting in the Gardo House to discuss a recent telegram sent from Washington, D. C., by territorial delegate John T. Caine. Caine had learned that the government would not accept the Manifesto unless all church members officially affirmed it. The next day, at General Conference, Mormons unanimously voted in favor of the document. The Manifesto eased some of the tensions between Mormons and non-Mormons. Church leaders were cautiously optimistic that the government would eventually return their confiscated property and reinstate their rights as citizens.32

Further meetings were held in the Gardo House to discuss local, state, and national politics as well as religion. In these meetings, church officials frequently debated whether Utahns should align themselves with the national Democratic and Republican parties.33 Previously, the political parties in Utah had been the Mormon People’s party versus the non-Mormon Liberal party. Church leaders eventually came to the conclusion that the Mormons’ political solidarity had been a factor in creating gentile opposition to the church.34 In May or June of 1891, a special political meeting was held in the Gardo House. According to James Henry Moyle, who was present at the meeting,

We were there for some time, but little if anything was done until we were advised that George Q. Cannon, then on the underground, was to be present. We had not seen any member of the First Presidency of the Church for some time. . . . I can only remember the gist of what he said, but it was to this effect . . . “Our people think they are Democrats, but they as a rule have not studied the difference between the two parties. If they go into the Democratic Party the Gentiles will go into the Republican Party . . . and we will have the same old fight over again under new names. So, as many as possible of our people must go into the Republican Party.”

Moyle told Cannon that he had always had a strong preference for the Democratic party; Cannon reassured him that he should feel free to follow his conscience. Church leaders later published a statement encouraging Mormons to join the national parties, and they sent elders to various stake conferences to instruct the people along the same lines.35

In November 1891 Bishop J. B. Winder gave notice to the federal receiver, Frank H. Dyer, that Wilford Woodruff would vacate the Gardo House by the first of December. From 1887 to 1891, the church had paid the government more than $28,000 in rental fees for the use of its own property. During this time, church leaders had hoped the Gardo House would be judicially declared an official church parsonage, exempt from escheatment under the laws of the land. When no exemption materialized, Woodruff decided that he would rather move than continue to pay the $450 monthly rent. Upon learning of the church’s intent to leave the mansion, the receiver immediately advertised for a new tenant. In January 1892 the Gardo House was leased to the Keeley Institute for $200 per month, much less than the church had been forced to pay.36

The Keeley Institute was an organization founded in 1880 by Leslie Enraught Keeley for the treatment of alcohol and drug addiction. Keeley’s cure was allegedly made from “double chloride of gold,” but it was actually a composition of atropine, strychnine, arsenic, cinchona, and glycerine. Patients at the institute, who were gradually weaned from their habits, received periodic injections and ingested a dram of the formula every two hours. They were also required to follow a regime of healthful diet, fresh air, exercise, and sleep. However, Keeley’s treatment attracted little attention until 1891, when the Chicago Tribune published a number of articles praising his work and launching a wave of popularity for the treatment. Franchises using Keeley’s name sprang up across the United States, Canada, Mexico, and England.37

The franchise that rented the Gardo House was the only Keeley Institute in Utah and was considered the “most thoroughly equipped institute in the West.” Patrons were predominantly middle-class men, although “ladies” visiting the institute for treatment were assured of seclusion and privacy.38 The institute occupied the Gardo House for a little over one year.

In 1893 President Benjamin Harrison pardoned former polygamists and restored their civil rights. A joint resolution of Congress restored the church’s property.39 On August 15, 1894, Wilford Woodruff recorded in his journal, “I went to the Gardo with Cannon & Smith Clawson and Trumbo. The Building was badly damaged by the Keeley Institute.” The church expended more than $2,000 to clean and repair damages to the mansion.40 However, church leaders decided to discontinue using the Gardo House as an official church parsonage, and they made arrangements to rent the mansion to Mr. and Mrs. Isaac Trumbo.

A non-Mormon, Isaac Trumbo had been born in Utah Territory and moved to California as a young man. He became interested in Utah mining and railroad properties, and he visited Salt Lake City as Utah was fighting its sixth battle for statehood. Trumbo soon laid his business ventures aside and began an eight-year crusade for Utah statehood. He masterminded a successful public relations campaign that promoted favorable newspaper coverage, and he lobbied in Washington, D. C., for the repeal of anti-Mormon legislation and for statehood.41

Expecting that Isaac would be rewarded for his efforts by a senatorship, the Trumbos decided to leave California and establish their residency in Utah. As a favor to church leaders, the couple decided to move into the Gardo House and act as hosts for dignitaries visiting Salt Lake City. Emma Trumbo, along with her interior decorators, came to Utah ahead of her husband to prepare the mansion for occupancy. Her arrival caused a flutter of excitement among local society leaders who anticipated lavish, San Francisco-style socials at the Gardo House. The Trumbos spent months and great sums of money to redecorate the home and to transport many of their beautiful furnishings from their stately San Francisco residence.42

Isaac Trumbo and his wife rented the Gardo House for a number of years, but they moved back to San Francisco after Trumbo failed to realize his political aspirations.

An assortment of people, including church leaders and former members of the Mormon underground, took an interest in the project and came to view the restoration. One of the visitors toured the mansion with Emma and pointed out various places of concealment, such as hollowed walls and [p.18] mattresses, where polygamists had hidden from federal lawmen. He also called her attention to a crack in the boarded ceiling of the Gardo House’s tower through which fugitives had watched their pursuers.43

When Utah finally achieved statehood on January 4, 1896, Trumbo wrote a letter to church leaders reminding them of his great sacrifices and of his desire to become one of Utah’s first senators.44 He arrived in Salt Lake City on a Sunday, ostensibly hoping to avoid a brass band or crowd at the railway station. But when no such fanfare materialized, the Trumbos were chagrined, and they became somewhat bitter. Emma later recalled, “He might as well have chosen a week day, for all the difference it would have made. What the Mormons wanted was Statehood. Gratitude? That had flown to the mountain tops, and frozen there.”45

The lukewarm reception at the railway station was a harbinger of things to come. For a variety of reasons, Trumbo never became a senator. He had tried to curry the favor of both Mormons and non-Mormons and was distrusted by all. Many Utahns regarded him as a Californian interloper, motivated entirely by self-interest. Church leaders denied that any promises had been made to Trumbo for his services, and George Q. Cannon questioned his character. “He is not a person whose manners and characteristics we would desire to represent us,” he felt, “for he is very ignorant, and then he would be, no doubt, a boodler, accepting bribes for services which he would render.” Cannon was referring to the fact that Trumbo and some of his associates had been suspected in some circles of buying newspaper and delegate support.46

According to B. H. Roberts, there had always been a general understanding that Utah’s senatorships would be divided between Mormons and non-Mormons. It had also been assumed that territorial delegate Frank J. Cannon, son of George Q., would be elected as one of Utah’s first senators. Non-Mormons, believing that Mormons would have too much influence with Trumbo, supported another candidate.47 There is some evidence that Trumbo’s wife, who later wrote bitter and outrageous falsehoods about Utah, was also one of the causes of his unpopularity. Emma once acknowledged, “My husband said I always gave the Mormons much uneasiness; they never felt quite sure of me.”48

When their political dreams went unrealized, the Trumbos moved out of the Gardo House and returned to San Francisco. After their departure, William B. Preston, a member of the church’s presiding bishopric, sent them a bill for rent due on the mansion. The Trumbos, who claimed they had spent $17,000 on the home, were incensed. The problem was compounded when a San Francisco newspaper reported that Trumbo had been the church’s financial agent, using church money and property to further church goals.

Wilford Woodruff immediately wrote an apology to the Trumbos, and the church promptly made a $10,000 settlement with them concerning the Gardo House.49 Subsequently the First Presidency, at Trumbo’s request, issued a written statement that was published in the Deseret News on February 5, 1898. The statement eloquently came to the defense of both the church and Trumbo, denying the allegations that he had ever acted as church agent or used church funds for any purpose. The First Presidency concluded, “In the time of our deep distress, when bitterness and hatred were manifested against us in almost every quarter, Colonel Isaac Trumbo came to Utah, and showed an interest in our affairs. . . . It is sufficient to say that probably no single agency contributed so much to making Utah a State as the labors of Colonel Isaac Trumbo and his immediate friends.”50 In spite of his disappointments and misunderstandings with the people of Utah, Trumbo remained on friendly terms with Wilford Woodruff. The aged prophet visited Trumbo several times in his San Francisco home, and it was during one of these visits that he became ill and died, on September 2, 1898.51

Soon after the Trumbos vacated the Gardo House, Bishop J. R. Winder and Alfred William McCune called at church headquarters to visit with members of the First Presidency. McCune told them that he and his wife, Elizabeth, were building a new home and wished to rent the mansion for two or three years. Church leaders, relieved to find a suitable new tenant, accepted his offer and set the rent at $150 per month.52

McCune had initially made his fortune as a railroad contractor, but he later branched out into the timber and mining industries, owning business interests throughout Utah and in parts of Montana, British Columbia, and South America. McCune was respected by his contemporaries for his integrity, his congenial personality, and his generous donations to worthy causes. He was also civic-minded and, like Trumbo, politically ambitious. In 1899, he ran for the Senate as the Democratic candidate against Republican incumbent Frank J. Cannon and several other candidates. When none was able to get a majority of votes, the election went down in history as the time when Utah was unable to select or send a senator to Washington. McCune later tried again for the Senate but was defeated by Thomas Kearns.53

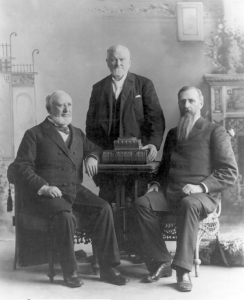

Alfred McCune arranged to rent the Gardo House while he and his wife were having a new mansion built.

Alfred McCune arranged to rent the Gardo House while he and his wife were having a new mansion built.

Elizabeth McCune had as many diversified interests as her husband had.She served in many prominent church positions and became close friends with Susa Young Gates, one of Brigham Young’s daughters. An active supporter of women’s rights, Elizabeth attended the 1889 International Congress of Women in London. After being voted patron of the organization, Elizabeth was entertained by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle.54

At the Gardo House, the McCunes repainted the interior, added many beautiful touches to its furnishings and fittings, and decorated the parlors and halls with marble statuary from Italy.55 While the family lived there, several of the children, little entrepreneurs like their father, set up a lemonade stand in front of the newly constructed Alta Club on South Temple. McCune was surprised and embarrassed when he discovered the stand on his way into the Alta Club with several business associates. He shut down the budding business and sent his children home.56

When they moved to their new house, the McCune Mansion at 200 North Main, the McCunes took with them all their furnishings and decorations from the Gardo House.57 The church, heavily in debt from the Edmunds-Tucker Act, decided to sell the Gardo House to Colonel Edwin F. Holmes at the sacrificial price of $46,000. When the transaction was completed in May 1901, a new era for the stately old home began.58

The mansion achieved the height of its glory while it was occupied by Holmes and his wife, Susanna Bransford Emery Holmes, who was famous as Utah’s “Silver Queen.” Susanna, or Susie, as she was known by friends, had come by her fortune through investments in Park City’s Mayflower and Silver King mines. A widow, she had been introduced to Colonel Edwin F. Holmes by Thomas Kearns, one of her business partners, in 1895. Although Susie was sixteen years his junior, the two discovered they had much in common and they began a lengthy courtship.59

Susie and Holmes were married in New York City on October 12, 1899. After a two-year honeymoon in Europe, the couple returned to Utah. Holmes purchased the Gardo House as a birthday present for his new bride. There were widespread rumors at the time of purchase that the couple planned to raze the mansion to make way for a more magnificent palatial residence. The rumors were quickly laid to rest, however, when they spent more than $75,000 to renovate and refurbish their new home.

During their travels in Europe, the Holmeses had purchased beautiful furniture, carpets, draperies, paintings, and bric-a-brac. The couple hired William J. Sinclair, an interior decorator with Chicago’s Marshall Field & Company, to redecorate the house, incorporating their acquisitions. Sinclair and his associates searched European and American cities for additional furniture, fabrics, and light fixtures for the mansion.60

On December 26, 1901, the Holmeses threw a lavish party to celebrate the completed renovation. The event was hailed by local newspapers as the most brilliant reception in the history of Salt Lake City. Elite, a society magazine published in Chicago, described several of the mansion’s forty-three rooms in detail.

The walls here [salon] are of old rose satin brocade and the woodwork of ivory enamel. A reseda green carpet covers the floors as background for rugs of priceless value in Persian silk and some skins of great beauty. . . . A second interior is of the dining room where the design is Gothic. The ceiling, woodwork and all the furniture are in Belgian oak. . . . At present the side walls are in dull gold glaze with bronze, dull greens, red and silver in Gothic design. . . . The carpet is of rich red, and the draperies are of red with application of cloth of gold. . . . Midway between the two rooms a Tiffany electric fountain is placed and the tables so arranged that upon feasting occasions the tables may be extended and united with the lovely fountain as a centerpiece. . . . In artistic equipment the house is magnificently magnificent.”61

The Gardo House soon became the gathering place for an elite, predominantly non-Mormon society that included Senator Thomas Kearns, Governor Heber M. Wells, financier D. H. Peery, and Perry S. Heath, owner of the Salt Lake Tribune. Fort Douglas military officers, clergymen, politicians, businessmen, educators, and the Holmeses’ relatives were also regulars at the mansion. Like other wealthy socialites of their time, the Holmeses set aside a day or two each week when they would be “at home” for friends and acquaintances to call–and they often received two to three hundred visitors a week. They were soon widely acknowledged as the reigning king and queen of Salt Lake City society.62

Now it was the Mormons’ turn to gaze at the Gardo House and wonder what went on inside. The children of church president Joseph F. Smith, who resided across the street in the Beehive House, wistfully watched the comings and goings at the Holmes residence. There were endless dinners, luncheons, receptions, teas, dances, card parties, and other events for them to observe. On some nights, the Holmeses put out a beautiful red carpet from their door to the end of the sidewalk to greet their expected visitors. The guests, men with big black capes and women in furs, always arrived in elegant horse-drawn carriages.63

Newspapers and magazines had a field day reporting social events at the Gardo House and chronicling the couple’s activities. Susie employed local musicians such as the Deseret Mandolin Orchestra, the Niles Mandolin Orchestra, chamber music groups, and popular vocalists to entertain at her social gatherings. She decorated the rooms of the mansion with carnations, roses, lilies, azaleas, chrysanthemums, tulips, palms, and syringa provided by Huddart Floral.64

The couple actively supported local social and cultural events. When famous entertainers visited the state, the Holmeses often held theater box parties at the Salt Lake Theatre or arranged for private performances in their home. On May 17, 1902, a local newspaper announced that Susie had hired worldwide-celebrated pianist Alberto Jonas for a musicale at the Gardo House. Jonas, who had received rave reviews for his performances at Carnegie Hall and with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, was the founder and director of the renowned Michigan Conservatory of Music. The Holmeses invited more than two hundred guests to the concert and arranged for Jonas to give another recital at the Salt Lake Theatre for the general public. His performance was considered to be one of the outstanding cultural events of the year.65

The Holmeses did not spend all their time socializing and entertaining. They were also occupied with civic affairs, real estate ventures, and frequent travel, closing the Gardo House to visitors when they were out of town. During the course of their travels through the United States, Europe, and Asia, the couple acquired many priceless pieces of art. In order to display their acquisitions, in 1903 they began planning a two-story building to the west of the Gardo House. The structure, which cost approximately $10,000, was completed in 1904. The ground floor was used as a garage, and the second floor was an art gallery, ballroom, and theater. On February 20, 1904, more than 400 guests were invited to attend the grand opening of the art gallery.

An immense flag made of red, white, and blue electric lamps was placed above the entrance to the mansion. The guests were welcomed in the drawing room by a receiving party that included the Holmeses, Governor and Mrs. Heber M. Wells, Mayor and Mrs. Richard P. Morris, Colonel and Mrs. John W. Bubb, and Mr. and Mrs. Fisher Harris. According to one newspaper account, “From 9 o’clock until midnight . . . the entire house was thrown open for the entertainment of the guests and the already beautiful rooms were made more beautiful by the use of many palms and cut flowers.” The Holmeses had also engaged a quartet and orchestra that performed in the drawing room and art gallery.66

The art gallery, considered by many to be the finest in the West, was “filled with the best works of old-world masters, as well as some of the finest examples of local artists’ productions.” The Holmeses also displayed porcelain sculptures, vases, Japanese embroidery, and an endless array of curios from all parts of the world. One of their most prized possessions was a $4,000 Steinway piano that they purchased in 1903. According to local newspapers of the period, the piano, nicknamed the “Aida” for the opera scenes painted on its lid and sides, was one of the most exquisite and costly pianos ever manufactured by the Steinways and was second only to art pianos made for celebrated Europeans. After the grand opening, the Holmeses made the art gallery available to the general public two days each week.67

The couple enjoyed their position as local society leaders for well over a decade. During the years immediately preceding World War I, they began spending more and more of their time at their California home, El Roble, near Pasadena. On June 6, 1917, a local newspaper announced that the Holmeses had decided to sell the Gardo House and move their treasures to California. They sent a California architect, whom they had previously hired to design a new residence, to Utah to examine the mansion. The purpose of his visit was to determine the feasibility of also removing the Belgian glass windows, black walnut interior finishing, and spiral stair casement from the Gardo House. The Holmeses were disappointed when the architect rendered the verdict that they would have to leave the fixtures behind.68

There was widespread speculation concerning the future of the Gardo House. Local newspapers published rumors that the mansion would soon be demolished to make way for apartments or an office building. There were also reports the couple was negotiating with Mormon church representative Charles W. Nibley for the church to repurchase the property. But the ultimate fate of the Gardo House was temporarily postponed when the Holmeses unexpectedly offered the mansion to the Red Cross until the end of the war. According to the Salt Lake Tribune, “Amelia’s Palace . . . was yesterday dedicated to the service of humanity and is to become the headquarters of the Red Cross and auxiliary workers of Salt Lake County–an army of volunteers that is expected to reach a total of 10,000 within the next few weeks.” Red Cross leaders, who had been in desperate need of a place where they could centralize their operations, regarded the mansion as “ideal” for the needs of their organization.69 On December 1, 1917, the Red Cross moved into the Gardo House and celebrated with a reception that included speeches and a brass band that played a variety of patriotic songs. William Spry, former governor of Utah, gave a tribute to the Holmeses and praised them for their long record of kindnesses and manifestations of unselfish spirit. More than two thousand people attended the event. It was estimated that between six and seven hundred young women from Salt Lake City eventually volunteered for service. 70

Red Cross workers were undoubtedly pleased to find the carpets, curtains, desks, tables, and telephones in shipshape condition, ready for immediate use. The Salt Lake Tribune described the Gardo House’s transformation:

The first floor is devoted to the executive and supply departments. The second floor has offices. . . . The large room to the east is the instruction room, where classes will be held . . . to the south and west is located what is to be known as the ‘transient room.’ This is regarded as one of the most important of facilities, it being planned that any transient or visitor who desires to do Red Cross work and who has not time to attend classes regularly may be supplied with materials and given the opportunity for work as desired. The art gallery and ball room have been transformed into the department of surgical dressings.”

Classes on elementary hygiene, home care for the sick, dietetics, first aid, knitting, and the making of surgical dressings were soon regularly held in the mansion.71

At the end of the war, the Holmeses resumed their efforts to find a buyer for the house, and on March 20, 1920, the LDS church bought it for $100,000. Two months after the transaction, the Red Cross vacated the mansion and moved its headquarters to the Utah State Capitol.72 The church intended to use the mansion to house the LDS School of Music, which the Deseret News called “one of the greatest schools of music in the West.” The school, which included piano, vocal, and wind departments, served as a training ground for the Tabernacle Choir. On October 2, 1920, the Deseret News reported that the church would also reopen the art gallery as a permanent exhibition hall for local artists.73

However, during the next few months, the church received a purchase offer from the Federal Reserve Bank. The bank, which was quickly outgrowing its quarters in the Deseret Bank Building, was seeking a new building site in the downtown area. On February 26, 1921, local newspapers reported that the church had sold the Gardo House to the bank for $115,000. Church leaders issued a statement assuring the public that the LDS School of Music would continue to function in a new locality and announcing tentative plans to place the Gardo House upon piles and move it, using rollers, to one of several sites that were under consideration.74

An article in the Deseret News a few weeks later gave further details concerning the plans to relocate the mansion:

The moving of one of Salt Lake’s old landmarks . . . may be one of the most spectacular events staged in the city, if the moving is found to be feasible. President Heber J. Grant said this morning he is having several streets of Salt Lake measured to see if there would be adequate passage way for the moving of the old Gardo House from its location on South Temple and State streets. When in San Francisco last week President Grant consulted one of the best known engineering experts in the country in regard to the moving of the building. This authority said it could be done easily provided five carloads of the necessary equipment could be shipped from San Francisco for the removal.75

There was widespread speculation on how and where the Gardo House would be relocated. All rumors came to an end on April 8, 1921, when newspapers announced that the mansion would not be moved and that it would soon be torn down. After researching and discussing the issue, church leaders had come to the reluctant conclusion that the moving expenses, estimated at over $20,000, were more than the church could afford and that the aging Gardo House, with its high ceilings, winding stairways, and outdated bathrooms, was too expensive to maintain.76

The Federal Reserve Bank had signed a contract with the Ketchum Builder Supply Company to raze the Gardo House, and on November 26, 1921, the Ketchum crew began to demolish the home. Efforts were made to salvage doors, windows, mirrors, fixtures and other valuable items from the mansion. These souvenirs were later sold at auction and many of them were scattered throughout Utah.77 A local newspaper, commenting several years earlier on the demolition of Brigham Young’s schoolhouse, had summed up the mood of the times.

The old Salt Lake is going. Slowly but surely the landmarks that bind the Salt Lake of history to the growing metropolis of the intermountain west are being torn down to the ground, and on the nude earth where they once stood are being erected modern structures, beautiful enough in design, but bare of historical interest.78

The Gardo House and its occupants played a pivotal role in Utah’s architectural, economic, political, and social history. The mansion, like other historical Utah landmarks, must never be forgotten.

Endnotes

*Sandra Dawn Brimhall is a writer living in Salt Lake City. Mark D. Curtis is an architect licensed in Utah and California. He resides in Sacramento, California. Photo captions were written by Alan Barnett, coordinator of the Utah History Information Center. All photos are from USHS collections.

1. Deseret News, November 28, 1921.

2. Susa Young Gates, “The Gardo House,” Improvement Era 20 (1917): 1099-1103; Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereafter JH), September 2, 1873 (microfilm, LDS Church Historical Department, Salt Lake City); Clarissa Young Spencer and Mabel Harmer, Brigham Young at Home (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 219-21. Other accounts say that the house was called “Gardo” because it seemed to stand “guard” over the city. The Beehive House was a residence for Young’s wives, as was the adjacent Lion House.

3. Paul Anderson, “William Harrison Folsom: Pioneer Architect,” Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (1975): 241, 247, 251; Gates, “The Gardo House,” 1099-1103; Nina Folsom Moss, A History of William Harrison Folsom (privately published biography, 1973), 37-44, copy in authors’ possession.

4. Susa Young Gates, The Life Story of Brigham Young (New York: Macmillan Company, 1930), 350-53.

5. See Eugene Traughber, “The Prophet’s Courtship: President Young’s Favorite Wife, Amelia, Talks,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 11, 1894, typescript copy, MS A-578, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City. Most of the gossip concerning Amelia appears to have originated with Ann Eliza Webb Young, who divorced Brigham Young in 1876. Ann Eliza claimed that Amelia demanded to be “first wife,” insisted on her own home, and was pampered, ill-tempered, and despised; see Leonard J. Arrington, Brigham Young: American Moses (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1985), 421.

At Amelia’s funeral, Brigham’s son Richard W. Young said, “She [Amelia] came into the family of President Brigham Young when he was nearly 60 years of age while she was young and attractive, but blessed with a mental grasp of the problems of the day. President Young’s health was enfeebled on account of an onerous life and he needed great care. Aunt Amelia was a natural nurse and performed the duties expected of her in a most praiseworthy manner. . . . From these incidents came the report that Amelia was President Young’s most favored wife. He however was an absolutely just man. . . . As the years grew on, however, the family learned to love Aunt Amelia. She was so just, so fair that I can truthfully say that she had the love of every member of the family.”

Heber J. Grant, who was also a speaker at the funeral, echoed these sentiments. He said, “I believe no higher tribute could be paid Sister Amelia than the fact that President Brigham Young’s wives loved his young wife.” Deseret Evening News, December 15, 1910.

In the Traughber interview, Amelia was quoted as saying, “I can’t say he [Brigham Young] had any favorites,” but privately she told friends she believed that Emmeline Free Young was Young’s favorite wife; see California Inter-Mountain News, August 9, 1949.

6. George Reynolds, Salt Lake City, June 6, 1876, to Brigham Young, Letter Books, Brigham Young Papers, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

7. Joseph Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 29 (1979): 54-63.

8. Melvin L. Bashore, “The 1876 Arsenal Hill Explosion,” Utah Historical Quarterly 52 (1984): 247-49; Salt Lake Herald, April 6, 1876.

9. George Reynolds, Salt Lake City, May 20, 1876, to Brigham Young, Letter Books, Brigham Young Papers.

10. Leonard J. Arrington, “The Settlement of Brigham Young’s Estate, 1877-1879,” in Pacific Historical Review 21(1952): 11-13. According to Arrington, it was discovered during probate of the estate that Young owed one million dollars to the church. One of the credits the church granted the estate against this indebtedness was a $120,000 credit for the Gardo House. Interview by Sandra Dawn Brimhall with Dr. Dee L. Folsom, Salt Lake City, Utah, September 23, 1990; notes in Ms. Brimhall’s possession. Harriet Amelia Folsom Young resided the rest of her life at a house at 1st West and South Temple. She never remarried. She is buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

11. Brigham H. Roberts, The Life of John Taylor: Third President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons Co., 1892), 331.

12. JH, December 27, 1881

13. Levi Edgar Young, “Historic Buildings of Salt Lake City,” Young Women’s Journal 6 (1922): 309-11. Several writers estimated that the church expended between $30,000 and $50,000 to finish the building and furnish its interior. Wilford Woodruff estimated the cost at $15,000; see Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 1833-1898, 9 vols. (Salt Lake City, Signature Books, 1989), January 2, 1882, entry. Salt Lake Tribune, February 3, 1957. JH, September 2, 1873, gives the dimensions of the house. The Tribune article claims that Ralph Ramsey, a famous Utah woodcarver, did some of the woodwork in the Gardo. Ramsey had done woodwork in the Beehive House and Lion House and had carved the eagle on Eagle Gate. However, he moved from Salt Lake City to Richfield in 1874, which may have precluded him from working on the Gardo House. In addition, it has been noted that the style of the woodwork in the Gardo was dissimilar to that of Ramsey’s work.

14. JH, January 3, 1882. Moses Thatcher, William Jennings, Angus M. Cannon, and their wives were particularly noted as being among the guests. Also noted were Joseph F. Smith, Franklin D. Richards, Francis M. Lyman, John H. Smith, and Daniel H. Wells. Matthias F. Cowley, ed., Wilford Woodruff: History of His Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1964), 545.

15. Roberts, Life of John Taylor, 331.

16. Kate B. Carter, ed., “Journal of Rachel Emma Woolley Simmons,” in Heart Throbs of the West, 12 vols. (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1939-51), 11:179.

17. Salt Lake Daily Tribune, January 1, 1882.

18. JH, January 5, 1882.

19. Deseret News, January 5, 1882.

20. James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 381; Roberts, The Life of John Taylor, 331.

21. Wilford Woodruff Journal, November 27, 1882, as cited in Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.” The Edmunds Act amended the Morrill Antibigamy Act of 1862, which had outlawed polygamy, disincorporated the church, and prohibited it from owning more than $50,000 worth of property not directly used for religious purposes.

22. Bruce A. Van Orden, The Life of George Reynolds: Prisoner for Conscience’ Sake (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 121-24. The first of these revelations was received on October 13, 1882. In it, George Teasdale and Heber J. Grant were called to fill two vacancies in the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and Seymour B. Young was asked to serve as one of the first seven presidents of the Seventies priesthood quorum. The revelation also called for increased missionary work among the various Indian tribes in the West and for a general reformation among priesthood bearers and church members. The second revelation, received in April 1883, reorganized the Seventies quorums throughout the church. John Taylor, Journal of Discourses, reported by G. D. Watt (1886; reprint Salt Lake City: Brigham Young University, 1967), 26:153-54; Roberts, The Life of John Taylor, 485.

23. Journal of John M. Whitaker, May 21, 1886, as cited in Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.” Joseph F. Smith, who later became sixth president of the LDS church, met and courted one of his plural wives, Mary Schwartz, while hiding at the mansion; Mark Curtis interview with Edith Smith Patrick, daughter of Joseph F. Smith, April 26, 1984, Bountiful, Utah, copy in Mr. Curtis’s possession and in LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City.

24. Roberts, The Life of John Taylor, 490; Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

25. JH, March 13, 1885.

26. Journal of John M. Whitaker, May 21, 1886. In his journal, Wilford Woodruff recorded the details of another raid, which he regarded as one of the most important events of his life. On February 8, 1886, he and other apostles held a meeting in the church historian’s office. During the meeting, approximately twenty federal marshals surrounded the church historian’s office and the Gardo House. As Woodruff believed that he and Erastus Snow were the only two persons liable to be arrested, the two men locked themselves in a small bedroom. They waited more than an hour while marshals made a thorough search of the Gardo House, Lion House, Beehive House, president’s office, and tithing office. When the marshals turned their attention to the historian’s office, Woodruff prayed to the Lord to direct him. When he finished his prayer, “Brother Jenson stept in to the Room with his glasses on. I put my Glasses on. I said to Brother Jenson I will walk with you across the street to the other Office. We walked out the door to the gate together. There was a Marshal [on] each side of the Gate & a Dozen more on each side of the side walk leading to the Gardo. . . . And the Eyes of all the Marshals was Closed By the power of God. . . . The saints knew me. The Marshals did not. . . . I recognized No one nor paid attention to any one. The dangerous feature of the operation was the Eyes of all the Brethren in the Streets followed me from [the] time I left the Historians office untill I Entered the Presidets office. . . . When I shut the door of the Clerks office Behind me I felt to shout Glory Halluluhuh though I said Nothing ownly thank God.” Erastus Snow also eluded the lawmen. See Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 8:376.

27. Quoted in Roberts, The Life of John Taylor, 392-400.

28. Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Latter-day Saints, 1890-1930 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 3-11; Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 8:449. Brian H. Stuy, ed., Collected Discourses, Vol. 1 (1886-89) (Burbank, CA: B. H. S. Publishing, 1987), 39.

29. B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols. (Orem, Utah: Sonos Publishing Inc., 1991), 6:194-96. Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, 8:508; Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1958), 368; JH, November 17, 1921; Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

30. L. John Nuttall Diary, November 24, 1889, as cited in Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

31. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 3-11; Roberts, Comprehensive History, 6:218-19; Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 297; Doctrine and Covenants of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1989), 291-92.

32. Abraham H. Cannon Journal, October 5 and 7, 1890, as cited in Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

33. Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

34. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition, 3-11.

35. James Henry Moyle, Mormon Democrat: The Religious and Political Memoirs, ed. Gene Sessions ([Salt Lake City]: Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1975), 177-81.

36. JH, November 13, 1891; Deseret Evening News, January 4, 1892.

37. Mark Edward Lender, The Dictionary of American Temperance (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1984), 270-72; Cheryl Krasnick Warsh, “Adventures in Maritime Quackery: The Leslie E. Keeley Gold Cure Institute of Fredericton, N. B.,” Acadiensis 17 (1988): 108, 117, 122-23; James T. White, The Dictionary of American Biography (New York: Scribner’s, 1936), 335-36. Leslie Enraught Keeley was born in Ireland May 4, 1834. His parents moved to Quebec in 1835, and when he was a young man Keeley moved to Beardstown, Illinois, where he studied medicine with a physician. During the Civil War, he served as an assistant surgeon with an Illinois regiment, participated in Sherman’s March to the Sea, and was captured by the Confederates. Keeley completed his medical degree in Chicago in 1864. He eventually settled in Dwight, Illinois, where he engaged in the general practice of medicine. In 1879 he announced that he had discovered a cure for alcohol and drug addiction. The following year, he established in Dwight the first Keeley Institute.

Keeley carefully avoided the appearance of quackery by employing only physicians at his establishments and by keeping the cost of treatment as low as possible. The program was one of the first in the nation to recognize alcoholism as a disease and to offer rehabilitation instead of punishment. Yet the “gold cure” was the most controversial alcohol treatment of its time. Opponents argued that there was no such substance as “double chloride of gold” and warned of possible side effects such as rashes, fatigue, weight loss, mental confusion, and even blindness. Despite such warnings, more than 400,000 individuals enrolled in the program, which was endorsed by churches and temperance workers. According to Warsh, “the system was successful for a great many alcoholics” because of “the mutual support, non-judgmental attitudes, and recapture of lost dignity” that it provided, not because of the formula.

Keeley Institutes flourished until Keeley died, leaving an estate valued at one million dollars. By 1936 only the parent institution in Dwight, Illinois, and a branch in Los Angeles, California, were in operation. We have been unable to locate any current listings for Keeley Institutes.

38. Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1902.

39. Thomas Alexander, Utah: The Right Place (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 1995), 205.

40. Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, vol. 9, 315, 327.

41. Edward Leo Lyman, “Isaac Trumbo and the Politics of Utah Statehood,” Utah Historical Quarterly 41 (1973): 129-30, 135, 142-49. Trumbo was born in 1858 at Carson Valley, located in the Nevada section of the Utah Territory. Although his grandfather, Col. John Reese, was a Mormon, Trumbo’s mother married outside of the religion, and he grew up without ever affiliating with it. During his childhood, his family moved to Salt Lake City, where one of their neighbors was Hiram B. Clawson, a cousin of Trumbo’s mother and one of the city’s most prominent men.

In California Trumbo made his fortune through successful mining and business ventures. He also joined the national guard, where he achieved the rank of colonel, a title he used throughout his life. In 1887 he and Alexander Badlam, another California businessman with a Mormon heritage, visited Washington and met with Utah congressional delegate John T. Caine. They expressed sympathy for the Mormons and the hardship caused by the newly passed Edmunds-Tucker Act. On their return trip to California, the two men visited Utah to explore mining and railroad properties and to visit church leaders. Trumbo’s interest in Utah was probably renewed by his relationship with Hiram B. Clawson, who was also involved with mining interests in Eureka, Utah. It was at this time that Trumbo became interested in statehood.

42. JH, September 17, 1899; The Argus, September 22, 1894, as cited in Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

43. JH, September 17, 1899.

44. Lyman, “Isaac Trumbo.”

45. JH, September 17, 1899.

46. A. H. Cannon Journal, November 21, 1895, in Lyman, “Isaac Trumbo.”

47. Roberts, A Comprehensive History, 6:338-40.

48. Salt Lake Tribune, September 17, 1899.

49. Lyman, “Isaac Trumbo.”

50. JH, February 5, 1898.

51. Lyman, “Isaac Trumbo.” Trumbo spent the remainder of his life in San Francisco. In 1911, he was evicted from his home for failure to pay an $18,000 mortgage debt. He was eventually forced to auction off many of his furnishings and art treasures, which were valued at $200,000. On November 2, 1912, Trumbo was the victim of a brutal beating and robbery and was left for dead on a San Francisco street. He never regained consciousness. Emma Trumbo remarried after her husband’s death.

52. JH, September 17, 1897.

53. See Stewart L. Grow, “Utah’s Senatorial Election of 1899: The Election that Failed,” Utah Historical Quarterly 39 (Winter 1971): 30-39. Of all the candidates, McCune came closest to winning. As the possibility of his victory grew stronger, however, a Republican legislator accused McCune of trying to buy his vote. Investigations into the charges did not substantiate them, but the damage had been done. See also George M. McCune, “Alfred William McCune” (privately published biography, 1972, photocopy in authors’ possession). Alfred William McCune was born July 11, 1849, at Fort Dum Dum, near Calcutta, India. His parents, Sergeant Matthew McCune and Sarah Elizabeth Caroline Scott McCune, were British transplants to India, where Matthew served in the Bengal Artillery of the East India Company. The McCunes were introduced to Mormonism by two English sailors and were baptized in India in 1851.

The family emigrated to America in 1856 and eventually made their way to Utah. McCune spent his boyhood years in Nephi, where he and his family, who had lived an aristocratic lifestyle in India, were compelled to become farmers. When the Union Pacific branch of the transcontinental railroad came to Utah in the late 1860s, McCune and his brothers found profitable employment as freighters and graders for the railroad. On July 1, 1872, he married Elizabeth Ann Claridge, his childhood sweetheart.

54. Ibid.

55. Levi Edgar Young, “Historic Buildings of Salt Lake City,” 309-11.

56. Interview by Sandra Dawn Brimhall with Jay Quealey, grandson of A. W. McCune, 1990, Salt Lake City, Utah; notes in Ms. Brimhall’s possession.

57. Gates, “The Gardo House,” 1099-1103. Alfred William McCune and his wife resided in the McCune Mansion until 1920, when they moved to Los Angeles. When they left Utah, the couple donated their beautiful home to the LDS church. The church later converted the mansion into the McCune School of Music and Art.

President Heber J. Grant noted in a speech that many people had attempted to persuade him to move into the McCune Mansion and use it as the official residence of the church president. Grant declined the offer, considering it a waste of church members’ money; see Gospel Standards: Selections from the Sermons and Writings of Heber J. Grant, comp. G. Homer Durham under the direction of John A. Widtsoe and Richard L. Evans, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City. The church’s acquisition of the McCune Mansion, which was newer and more modern than the Gardo House, may have been one of the factors in the church’s decision to demolish the Gardo House.

After the death of his wife in 1924, McCune moved to France, where he resided until his death in 1927. At the time of his death, his estate was valued at fifteen million dollars. The McCunes are buried in Nephi, Utah.

58. JH, May 6, 1901; Gates, “The Gardo House,” 1099-1103.

59. Susanna was born May 6, 1859, in Richmond, Missouri. She crossed the plains when she was five years old and spent her youth in Plumas County, California. In 1884 she made an extended visit to Park City to visit friends. It was there that she met and married her first husband, Albion B. Emery. Emery, who was originally from Maine, emigrated to the West in search of gold in 1869. He eventually moved to Tooele, Utah, where he was elected by the Liberal party as Tooele’s first non-Mormon county clerk and deputy recorder. In 1880 Emery moved to Park City, where he worked at a variety of jobs, eventually becoming one of the town’s leading citizens.

The couple became wealthy from investments in Park City’s Mayflower and Silver King mines. When Emery died prematurely on June 16, 1894, from heart and liver disease, Susie and their adopted daughter, Louise Grace, became heirs to his estate. Susie proved to be an astute and tough-minded businesswomen. It was reported that she managed her money into a vast fortune.

Holmes was a widower and a wealthy businessman who had made his fortune in the lumber and mining industries. He was born August 8, 1843, in Orleans County, New York, and was largely a self-educated and self-made man. During the Civil War, Holmes enlisted as a private in the Union Army and was eventually promoted to the rank of captain. Like Trumbo, he preferred to be addressed as “colonel,” an honorary title, throughout his life.

For a comprehensive history of the Silver Queen, see Judy Dykman and Colleen Whitley, The Silver Queen: Her Royal Highness Suzanne Bransford Emery Holmes Delitch Engalitcheff (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1998). Dykman and Whitley believe that Susie’s fortune was much less than the fifty million dollars reported by eastern and local newspapers.

60. Elite, March 15, 1902; Heinerman, “Amelia’s Palace.”

61. Salt Lake Tribune, December 27, 1901; Elite, March 15, 1902; Silver Queen Scrapbook, 1902-1904, Utah State Historical Society, MIC A-633.

62. Interview by Sandra Dawn Brimhall with Susanna Harris Hartman, California, October 2, 1990; notes in Ms. Brimhall’s possession. Silver Queen Scrapbook.

63. Edith Smith Patrick interview.

64. Peter T. Huddart, the premier florist of the period, had apprenticed under the head floral director for the Prince of Wales. See Silver Queen Scrapbook and JH, January 1, 1902.

65. Deseret Evening News, May 17, 1902; Silver Queen Scrapbook.

66. Silver Queen Scrapbook.

67. Ibid.

68. JH, June 6, 1917.

69. Ibid., November 20, 1917.

70. Ibid., December 1, 1917; Mrs. W. Mont Ferry, E. O. Howard, R. J. Shields, History of the Salt Lake County Chapter of American Red Cross, 1898 to 1919, 10. Photocopy of unpublished MS in Ms. Brimhall’s possession.

71. JH, December 1, 1917, November 28, 1921.

72. Deseret Evening News, March 20, 1920, May 4, 1920. Colonel Holmes and Susie lived in their California home, El Roble, until Holmes’s death in 1925. In 1930, Susie married a Serbian doctor named Radovan N. Delitch. The marriage ended in divorce two years later, and Delitch later hanged himself in his cabin during an ocean cruise. Shortly after his death, Susie sold El Roble and auctioned off her Rolls Royce, furniture, paintings, and the famous “Aida” piano. In 1933 she married Prince Nickolas Engalitcheff. The couple spent most of their time in California and Europe until Engalitcheff’s death in 1935. When Susie died in 1942, at age 83, she had spent almost all of her fortune. At her request, she was buried in Salt Lake City’s Mount Olivet Cemetery alongside her first husband, Albion B. Emery. Legend has it that for many years the exact location of her grave was kept a secret because of the persistent rumor she was buried in a silver dress and that there were silver dollars in her coffin.

73. Deseret News, April 28, 1920; JH, October 2, 1920.

74. Deseret News, February 26, 1921. According to the Improvement Era 29 (1925-1926): 517, “The work of breaking ground for the Federal bank building, corner of South Temple and State St., began on January 25, 1926.” The Federal Bank Building has now been demolished; the site is occupied by the twenty-six-story Eagle Gate Plaza and Tower, which was constructed in 1986.

75. JH, March 10, 1921, March 26, 1921.

76. Ibid., April 8, 1921.

77. Ibid., November 17 and 28, 1921.

78. Silver Queen Scrapbook. Robert Parson, “Seeps, Springs, and Bogs: The Changing Historic Landscape of Smithfield,” pp. 38-54