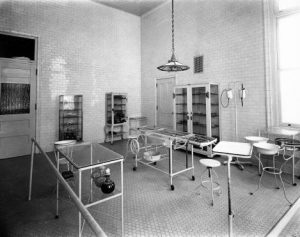

Holy Cross operating room, December 12, 1908

Yvette D. Ison

History Blazer, February 1995

In the last quarter of the 19th century Utah faced rapid economic and social change. Many areas of life were affected. By the 1870s improved medical service was needed in the territory. Those physicians who had immigrated to Utah in the early settlement period were growing old. Moreover, the large number of new arrivals in Utah created a demand for more doctors and midwives as well as hospitals. Home care was no longer adequate.

Among Mormons the initiative for medical reform began within the Relief Society. Responding to the request of several women for a maternity hospital and obstetrical training, the Relief Society subsidized six women to attend eastern colleges and receive medical degrees. One of the eastern-trained physicians, Romania Pratt, returned in 1877 to develop a medical training school in Salt Lake City. Women could attend the six-month program for a fee of $50 for tuition and boarding at Pratt’s home.

Other religious groups also entered the medical field, creating hospitals in Salt Lake City. In 1874 Episcopalians opened St. Mark’s Hospital. Two years later the Holy Cross Hospital was established by the Roman Catholic Sisters of the Holy Cross.

St. Mark’s Hospital

The Relief Society followed suit in 1882 with the formation of the Deseret Hospital with Dr. Romania Pratt and Dr. Ellen Ferguson as the physicians. Two male doctors were later included on the staff. The Deseret Hospital served as a women’s medical school, emergency hospital, and maternity home. In 1877 the hospital opened a school of nursing and obstetrics. Each year up to six women were trained in these fields.

The Deseret Hospital ran into financial trouble, however, because of its payment policy. The Relief Society had relied on donations to the hospital fund to allow patients to receive care regardless of their ability to pay. Learning that care was free, even patients able to pay for treatment often refused to do so. Financial instability finally toppled the institution.

But setting up hospitals and training doctors at prestigious medical schools in the East and locally were only part of the health care scene. Utahns, no longer culturally isolated, also responded to national fads and seemed to be particularly attracted to certain health crazes.

A brief skim over advertisements in the Deseret News of January 1896 shows that good health was a major marketing tool. Hood’s sarsaparilla, for example, was boldly declared to be “The only true blood purifier” because it cured “cramps and stomach ache.” Manyou’s Cure boasted more expansive results. In addition to purifying the blood and “restoring lost power to weak ones,” its uses included cures for rheumatism, asthma, nerve problems, and even “female ailments.”

Some companies devoted their product line to curing “Female Sickness.” An ad for Dr. David Kennedy’s Favorite Remedy explained that the disease suffered by thousands of women included such symptoms as nervousness, fragility, weak nerves, and “an awful internal trouble that is wearing out their lives.” Dr. Miles’ Nervine ad noted that women’s ailments caused irritability, fretfulness, ringing in the ears, and sleepless nights.

Some medicines promised a cure for diseases suffered by specific age groups. Castoris for Infants claimed to destroy worms, prevent vomiting sour curd, relieve teething, cure constipation, and neutralize “poisonous air.” Paine’s Celery Compound, described as the wonder drug for the elderly, published testimony from a 99-year-old woman who had remained healthy by taking daily doses. Celery Compound worked its wonders by replacing “worn-out parts” with “healthy, new ones.”

Not only were cures popular in the marketplace, Utah’s medical experts also discussed at length new approaches to health. The Salt Lake Sanitarian, a magazine published from 1888 to 1891, offered insights into health trends of the era. An article in the July 1889 issue explained that baldness among men was a result of the scalp’s lack of adequate sunlight. To prevent baldness, the article suggested that men wash their heads thoroughly at least once a week, never wear unventilated hats, and seldom smoke.

An article in July 1888 described coffee as twice as bad for the body as a half-pint of light wine taken daily. In another article tobacco’s bad effects included enfeebling the nervous system, weakening the stomach, disturbing sleep, damaging mental capacities, and causing long fits of melancholy. Drinking tea caused cold feet.

The magazine also questioned lifestyles. In its November 1890 issue the Sanitarian boldly declared that neglecting to provide dry rooms and beds for guests was the cause of numerous diseases and equal to murder and suicide—surely a frightening thought for prospective hosts! In May 1889 a female physician identified heavy corsets as the cause of spinal deformities among women and birth failures.

Although such explanations may seem absurd to the modern reader, today’s health industry continues with the same energy that marked its beginning. The hospitals, remedies, and publications of the late 19th century only represent Utah’s introduction into the shifting market of America’s health industry.

Sources: Jill Mulvay Derr, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992); Salt Lake Sanitarian, Utah State Historical Society Library; Deseret News.