Robert S. McPherson

History of San Juan County

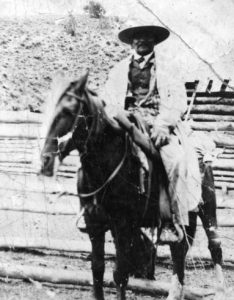

Chief Posey

The volatile situation—what has been called the “Posey War” and the “Last Indian Uprising”—occurred because of a relatively insignificant affair that started when two young Utes robbed a sheep camp, killed a calf, and burned a bridge. The culprits voluntarily turned themselves in, stood trial, but then escaped from the sheriff’s grasp. The townspeople moved quickly to get not only the two boys but Posey as well, who by this time had become synonymous with all of the ill will felt between these factions. To the white people, he was the living symbol of all degraded or troublesome Indians.

The newspapers played a significant role in developing this attitude, making Posey the lightning rod waiting to be struck. His name had appeared, in either direct or indirect accusation, with almost every bothersome incident that occurred. People often cited his band of Utes as the culprits in a misdeed; Posey was said to have been the man who killed Joe Aiken, the white fatality in the 1915 fight; he reportedly murdered his brother Scotty because the latter wanted a peaceful settlement of that conflict; he had also killed his wife by accident, though many settlers refused to believe it was a mishap; he resisted living on the reservation; and he was such a colorful character that his threats, cajoling, and antics often brought a strong reaction to what would normally have been forgiven. Thus, the 1923 “war” served as the means by which this “evil” could be exorcised.

The actual events of the conflict have been documented elsewhere, but in terms of the coverage of the press it was described in the finest tradition of hysterical, World-War-I-era yellow journalism. The prose is too voluminous to recount in detail here, but glimpses of it show its general tenor. On 22 March the Times-Independent noted that “Piute Band Declares War on Whites in Blanding” and reported that the county commissioners had sent a note to Utah governor Charles Mabey requesting a scout plane armed with machine guns and bombs. Supposedly, members of the posse had five horses shot out from beneath their riders, the men feared that four of their number had been ambushed, and “the most disquieting feature is the fact that Old Posey, the most dangerous of all the Piutes, is in charge of the band.”

In reality, there was little to the situation beyond a massive exodus of Utes and Paiutes fleeing their homes to escape into the rough canyon country of Navajo Mountain. Posey fought a rearguard action to prevent capture, was eventually wounded, and watched his people get carted off to a barbed-wire compound set up in the middle of Blanding. He died a painful death a month later from his gunshot wound.

The newspapers continued to report that the State of Utah had put a $100 reward—dead or alive—on Posey, now charged with insurrection, a crime punishable by death. C. F. Sloane of the Salt Lake Tribune stayed in Blanding and fired off press releases with a thin veneer of truth covering a mass of outright lies. He wrote that Blanding had been surrounded during “thirty-six hours of terrorism,” with Indians in war paint riding the streets; he claimed that Posey, “the red fox,” was forming a “mobile squadron,” that there was a well-planned Paiute conspiracy that included robbing the San Juan State Bank, and that there were “sixty men skilled in the art of mountain warfare awaiting the call to service.”

The newsmen covering the incident gave the town a military character: “Blanding since the outbreak has become more or less an armed camp. It wears the aspect of a military headquarters. The arrival and departure of couriers from the front is a matter of public interest.” However, the citizens of Blanding were not fooled. Many of them kidded the reporters about their coverage of the incident; but this had little effect. When one person asked a correspondent why he was not writing the truth, he gave a very simple answer: “We’re not ready to go home yet, and if we don’t keep something going, we’ll be getting a telegram to come home.”

Reporters found Posey’s death just as dramatic as had been his life. One newsman said that Posey had been killed in a flash flood that flushed him down a canyon. Another believed he had died of natural causes; some Utes believed that poisoned Mormon flour had done the job. The generally accepted explanation was that he had died from blood poisoning incurred by the gunshot wound. Regardless of the cause, the newsmen could report with finality that Posey had gone to the “happy hunting grounds.” They also mentioned that many of the Utes were content that Posey had “gone beyond,” while the whites vied to have the best stories to come out of the war.

When Posey’s death was certain, some of the Utes took Marshal J. Ray Ward to the body’s location in order to certify the death. The law officer buried the corpse and disguised the grave, but to no avail. Men who wanted to have their picture taken with the grisly trophy exhumed the body at least twice. A forest ranger, Marion Hunt, claimed in the newspaper that he had found the body during a routine range examination a few days before Marshal Ward ever appeared on the scene. It seems as though everyone wanted some type of claim in the matter.

Of greater import was the solution to the question of who controlled the ranges. The Posey incident served as an excuse for officials to force land allotments on the Utes. Hubert Work, Secretary of the Interior, issued an order in April that both Ute groups stop their nomadic life and settle on individual land holdings. Moab’s Times-Independent reported, “Old Posey’s band, consisting of about 100 Indians, will be given parcels of land located on or near Allen Canyon while Old Polk’s band, numbering about eighty-five men, women, and children will be allotted land along Montezuma Creek. The two bands which are not friendly, will be located some distance apart.”

The number of allotments in Montezuma Canyon varied. Ira Hatch, who owned and operated a trading post in the area, estimated there were twenty-three Ute camps in Montezuma and Cross canyons. Today there are no Ute allotments in the former and only a few in the latter canyon, the tribe having bought many of the individual holdings. In Allen Canyon, individual Ute families still own thirty allotments.

While the Utes were losing their hold on Montezuma Canyon, the Navajos were successfully tightening theirs. Undoubtedly there had been small groups of Navajos who had lived in the canyon before 1900. One man named Dishface insisted his residency went back to 1888, while others were not far behind in their claims. The general Navajo population influx, however, occurred after 1900, as the Indians with their herds of sheep roamed in search of water and grass. By 1905 the Navajo agent stated that 250 Indians lived in a triangle of land that started at the mouth of Montezuma Creek, extended east to the Colorado border, south to the San Juan River, and then returned to Montezuma Creek. On 15 May 1905 the government added the land to the reservation by Executive Order 324A.

Friction between Navajos, Utes, and cattlemen continued into the 1920s. While the Navajos and Utes appear to have worked out an unofficial boundary at the intersection of Cross Canyon and Montezuma Canyon, with the Navajos remaining to the south, problems with the Bluff cattlemen became increasingly serious. Evan W. Estep, superintendent of the Shiprock Agency, noted that

the outside stockmen are crowding the Indians just about as hard as it is possible to crowd them and avoid trouble. . . .The present offenders are the younger stockmen and apparently the younger Mormons are not of the same caliber as their fathers were.

The underlying assumption of the cattlemen was that the Indians did not have the same right to the public lands as the white man. The solution to the problem again tied in with the Posey conflict; when A. W. Simington registered allotments for the Utes, he also did so for the Navajo. Of the thirteen family heads who filed for allotments in 1923, the average length of previous occupancy in the area was fifteen years, with a median of fourteen years; the shortest occupancy was two years and the longest thirty-five years.

Conflict over the ranges in the Montezuma Canyon area continued until it was divided in 1933. The Paiute Strip was officially added to the Navajo Reservation. For the Utes, it was a dead issue. They had already lost their ancestral lands ten years before. Fewer than a hundred Utes still remained off the Colorado reservation, sequestered along Allen Canyon and Cottonwood creeks, endeavoring to become twentieth-century farmers.

The Ute and Paiute experience between 1880 and 1933 was traumatic. Squeezed in a vise of Mormon and non-Mormon farming communities, livestock operations—both Anglo and Navajo, and an inadequate reservation, these Native Americans had no choice but to give up their hunting-and-gathering way of life. If they had been as fortunate as the Navajo—who had a number of aggressive agents to work on their behalf, an expanding population base, important economic interests to catapult them beyond a barter system, and a more docile reputation, then perhaps the story would have turned out differently. The Utes had none of these things. Instead, they were forced to fight for what was theirs. As a result, they lost most of what they had as their lands were taken and their way of life melted away in the crucible of the twentieth century.