John S. McCormick

Beehive History 20

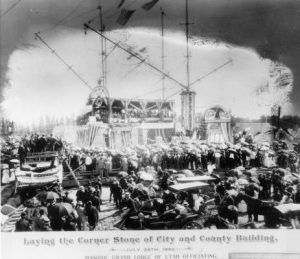

Laying the Cornerstone of the City and County Building on July 25, 1892

Since its dedication 100 years ago on December 28, 1894, the Salt Lake City and County Building has become firmly imbedded in the fabric of the community. In addition to housing the offices of local government, it is linked to important events in Utah’s history. The convention that drew up the Utah State Constitution met in it. State government used the building from 1896 until 1915 when the State Capitol was finished. It housed the first Salt Lake City Public Library. The murder trial of Joe Hill, labor radical and member of the Industrial Workers of the World, which drew national and international attention, was held in it in 1914. During the Great Depression when Utah’s unemployment rate registered as high as 36 percent, protest rallies drew several thousand to the building’s grounds. Visiting Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft spoke from its steps. It was also a tourist attraction from the first. People eagerly climbed its tower for the magnificent view. In June 1895 city and county officials hired George Lindell, a young African American, to supervise excursions to the tower and “to work for tips,” but “with instructions that no one need give him any tips for showing the clock and the landscape in general unless they felt like it.”

City and County Building under construction

The Salt Lake City and County Building was constructed on Washington Square between 1891 and 1894 at a cost of more than $900,000. The architectural firm of Monheim, Bird, and Proudfoot designed it in the Richardsonian Romanesque style made popular in the late nineteenth century by Henry Hobson Richardson. Behind these bare facts lies a fascinating story.

City and county officials first began to talk about building a combined city hall and county courthouse in the late 1880s. Each occupied relatively small separate structures. The Salt Lake City Hall at 120 East First South was a two-story building, sixty feet square, erected during 1864–65 of sandstone from Red Butte Canyon east of the city. Its designer, William H. Folsom, was one of Utah’s most important early architects. In addition to serving the city, the building periodically housed the territorial legislature, and the 1872 and 1882 Constitutional Conventions were held there. The Salt Lake County Courthouse, 268 West Second South, was designed by Mormon church architect Truman O. Angell, Sr. Completed in 1861, this two-story building was about the same size as City Hall. By the late 1880s both buildings had become too small to house local government in the fast-growing city and county.

City and County Building, May 7, 1902

In July 1889 city and county officials agreed to construct what was then and for several years afterward called the “Joint Building.” A building committee selected a site for the new structure on the southwest corner of First South and Second East. A few weeks later, however, they changed their minds and chose a site near City Hall on the southwest corner of First South and State Street. An architectural competition for the building’s design drew five contestants with C. E. Apponyi submitting the winning plan. No drawings of his proposal are known to exist, but the Salt Lake Herald of January 3, 1890, described it as a “handsome,” five-story Romanesque building, 60 feet by 150 feet, with two wings, tile floors, and a cement roof. The estimated cost was $150,000.

Excavation for the foundation began the first week in February 1890, but when new city officials took office they immediately questioned the project and on February 22 ordered all work stopped. The mayor—businessman George M. Scott—and a majority of the new council were members of the Liberal party and were the first non-Mormons elected to public office in Salt Lake City. At that time national political parties did not exist in Utah. Instead there was the anti-Mormon Liberal party and the Mormon church’s People’s party, both organized in 1870. During the 1890 campaign the Liberal party had attacked the People’s party for its decision to construct the Joint Building, calling the project extravagant and unnecessary. Nevertheless, after three months of controversy, the new administration decided to continue work on the building.

By November 1890 the foundation was in place. Then on November 11 all work stopped when the Joint Committee fired architect Apponyi as superintendent of construction, questioning his ability to do the job. Moreover, cost estimates had doubled from $150,000 to $300,000. A bitter debate ensued over whether to complete the building as designed by Apponyi or commission a new design, and it was divided very much along Mormon/non-Mormon lines.

Finally, at the end of March 1891, after nearly five months of debate, city and county officials decided to build an entirely new building on an entirely different site—Washington Square. Apparently City Councilman James H. Anderson first suggested this location. It too was controversial with the Deseret News, among others, claiming it was too far from the center of town and had been chosen mainly because some City Council members owned property nearby that would increase in value once the building was constructed.

The Joint Committee remained firm in its decision, however, and announced that a new architectural competition would be held. They advertised the competition locally and in Denver, San Francisco, and Chicago with a brief announcement: “Plans are invited for a Joint City and County Building to be erected in the center of the Eighth Ward [Washington] Square….The proposed building to have four fronts, three stories, with basement and construction on the plan of what is known as fire combustion. Cost of building complete not to exceed $350,000. All plans to be submitted on or before May 15, 1891. City and County reserve the right to reject any and all plans.” The competition drew 15 responses, among them Monheim, Bird, and Proudfoot, a new Salt Lake firm formed shortly before the competition when Henry Monheim, “the mentor of Salt Lake architects,” according to the Salt Lake Tribune, joined with two men who had been in practice together in the Midwest—George Washington Bird and William T. Proudfoot. The firm may have been organized specifically for the City and County Building competition, and on May 25 the committee announced it had chosen their entry as the winning design.

Monheim was born about 1824 in Prussia. Little is known about his life before 1870 when he came to Utah and settled in Corinne, the transfer point for freight and passengers north to Idaho and Montana from the recently completed transcontinental railroad. He designed several buildings there, including the Corinne Opera House. By July 1872 he had moved to Salt Lake City where he remained until his death on July 30, 1893, eighteen months before the City and County Building was finished. The Emanuel Kahn House, a striking Queen Anne structure at 678 East South Temple, and the former B’nai Israel Temple at 249 South 400 East are two of Monheim’s other designs that remain standing.

Proudfoot, who was born May 2, 1860, near Indianola, Iowa, began working for an architect in Des Moines after graduating from high school. Bird, born in New Jersey on September 1, 1854, was employed by the same architect. In 1882 the two men established their own practice and barnstormed for commissions throughout the Midwest. By 1885 they had moved to Wichita, Kansas, and in the next six years received commissions for nearly 100 buildings. When Wichita’s boom years ended in 1891 Bird and Proudfoot moved to Salt Lake City and formed a partnership with Monheim. In addition to the City and County Building, the firm designed at least 14 homes in Salt Lake, a small factory, and an apartment building. Bird and Proudfoot returned to Des Moines about two years after Monheim’s death. They became the principal architects for Iowa’s three state university campuses and also designed other public buildings.

To no one’s surprise the Joint Committee’s selection of Monheim, Bird, and Proudfoot and that firm’s winning design both generated considerable controversy. A year later, following the dedication of the building and the laying of its cornerstone, the Salt Lake Herald was still grumbling about it. The newspaper characterized the competition as unfair and called the design “a pretentious fraud.”

On September 22, 1891, the Joint Committee selected the construction firm of John H. Bowman, a well-known local contractor, even though his bid of $377,978 was only the third lowest. He had the support of local labor unions and the two lower bidders did not. By the spring of 1892 some 100 men were regularly at work on the building, and the contractor intended to increase that to between 150 and 200 by mid-May. In hiring, preference was given to married residents of the city and county, although City Councilman William P. O’Meara thought it wrong to discriminate against single men. They were likely to get as hungry as married men, he pointed out, and often had parents or sisters to support. Unskilled laborers received about $2.25 a day and skilled workers, such as stonecutters, got $4.50. Everyone worked nine hours, from 7:30 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with a half-hour for lunch, five days a week. Labor unions had urged an eight-hour work day on the project, but even nine hours was less than many people worked.

The cornerstone of the building was laid under the supervision of the Masonic Lodge on July 25, 1892, when the walls had been completed to a height of 38 inches. The ceremony began with a parade from City Hall to Washington Square and included Denhalter’s Band, Held’s Band, policemen and firemen on horseback, Masons and other fraternal organizations, and local, territorial, and federal officials and their invited guests in carriages. Thousands listened to prominent speakers, all of them non-Mormons, praise the building as a symbol of a new era marked by the end of Mormon church domination of political affairs and the triumph of civil government.

The building’s troubles were not over, however. By the summer of 1893, with the exterior finished and the roof completed, the Panic of 1893 began to take its toll. A nationwide depression that lasted until 1897 created widespread unemployment, and the revenue of both Salt Lake City and Salt Lake County fell, ultimately to nearly half. Construction was halted while officials reviewed the situation. Finally, they decided to go ahead with a reduced work force. Fourteen stained glass windows originally planned for the west facade were eliminated to save money.

Except for minor details the building was finished in November 1894. The first City Council meeting was held in it on November 19, and former council members as well as current ones attended. The Salt Lake City and County Building was dedicated on December 28. It was open all day to the public for tours, and at 3 p.m. a formal ceremony was held in the City Council Chambers. Wilford Woodruff, president of the Mormon church, gave the opening prayer. Then a group of civil and church dignitaries addressed the gathering. Although their rhetoric was flowery, all recognized an essential point. The process of constructing the building had been a long, expensive, and frustrating one, filled with division and controversy, but the result, as Judge Edward F. Colburn said, was “a magnificent structure” and a “monument to the architects who conceived its plan, a credit to the public officers who directed its construction, and imperishable evidence of the progressive spirit of the citizens who supported it.”

The building, which would become a historic and architectural landmark in Salt Lake City, captured people’s attention and delighted their imaginations from the beginning. Its appeal lay in a number of things: its size, shape, texture, rich ornamentation, fine interior spaces and workmanship, the relationship of its myriad parts to the whole, and the way it fit into its physical surroundings.

The clock tower rises an estimated 256 feet from ground level to the top of the statue Columbia. The rough-hewn grey sandstone on the exterior came from the Castle Gate-Kyune Junction area of Carbon County. The sixty exterior columns are made of granite. Slate for the roof probably came from Slate Canyon southeast of Provo. Walter Baird and his partner Oswald Lendi did most of the elaborate carving found on the exterior, particularly near the entrances. Indeed, the building seems alive with examples of the stone carver’s art, including human faces and figures, gargoyles, animals, monsters, roses, and scrolls. Many carvings depict real people, events, and themes in Utah history. At completion the building contained more than 100 rooms with oak doors, moldings, and wainscoting, and onyx wainscoting in the hallways. Many offices had marble-framed fireplaces.

A local nurseryman, Martin Christophersen, oversaw the landscaping. More than 10,000 flowers and shrubs were planted as well as 45 varieties of shade trees, including many rare and imported specimens. These plantings, along with fountains and walkways, gave the building a park-like setting.

About the time of the building’s completion Utahns elected 107 delegates to a Constitutional Convention. At the invitation of Salt Lake City and County officials it was held in the new building. The convention opened on March 4, 1895, and adjourned nine weeks later on May 8, having completed the final draft of the Utah State Constitution for voters to ratify in November. The convention delegates met in the building’s County Civil Courtroom. There was little space for spectators, and the delegates sat at tables with no drawers in which to keep their papers. Following a debate over seating arrangements the convention decided to let delegates age 60 and over choose their seats. Those remaining drew lots for theirs.

When statehood for Utah was finally achieved with the signing of the statehood proclamation by President Grover Cleveland on January 4, 1896, a large steam whistle sounded from the tower of the City and County Building, adding to the din created by shotguns, cannons, bells, fireworks, and shouting.

The City and County Building’s service to the state did not end with the Constitutional Convention. The State Legislature held its biennial sessions there. The Salt Lake Tribune described the first one in January 1896: “The Joint Building took on the air of a capitol yesterday, and all day long its spacious corridors echoed to the tread and conversation of groups of politicians, legislators, lobbyists, and office seekers. The legislative halls were made ready for occupancy, and senators and members were busy preempting desks and getting used to their quarters.” The offices of most state officials, including the governor, were also in the City and County Building until 1915, and according to Gov. William Spry, “Virtually all state business was conducted in it.”

By the 1980s, after decades of use and in need of extensive repairs, the City and County Building faced possible demolition. Controversy again swirled around the building as those who wanted the landmark structure restored battled those who favored tearing it down and erecting a new building. Salt Lake City residents apparently loved the old building and opted to restore it as the seat of city government (while county officials decided to build a new county complex at 21st South and State streets and move to it rather than remain in the City and County Building). The $30.3 million project, which began in the summer of 1986, was an enormous undertaking, took three years to complete, and included restoration of the exterior sandstone and the return of several rooms, including the City Council Chambers, to almost their original condition and decor. In addition, it was the first historic building in the world to be retrofitted with a base isolation system to cushion it during an earthquake. Architects for the project were the Ehrenkrantz Group of San Francisco and Burtch W. Beall, Jr., of Salt Lake City. The building was reopened with a three-day celebration on April 28–30 that included public tours and special events.